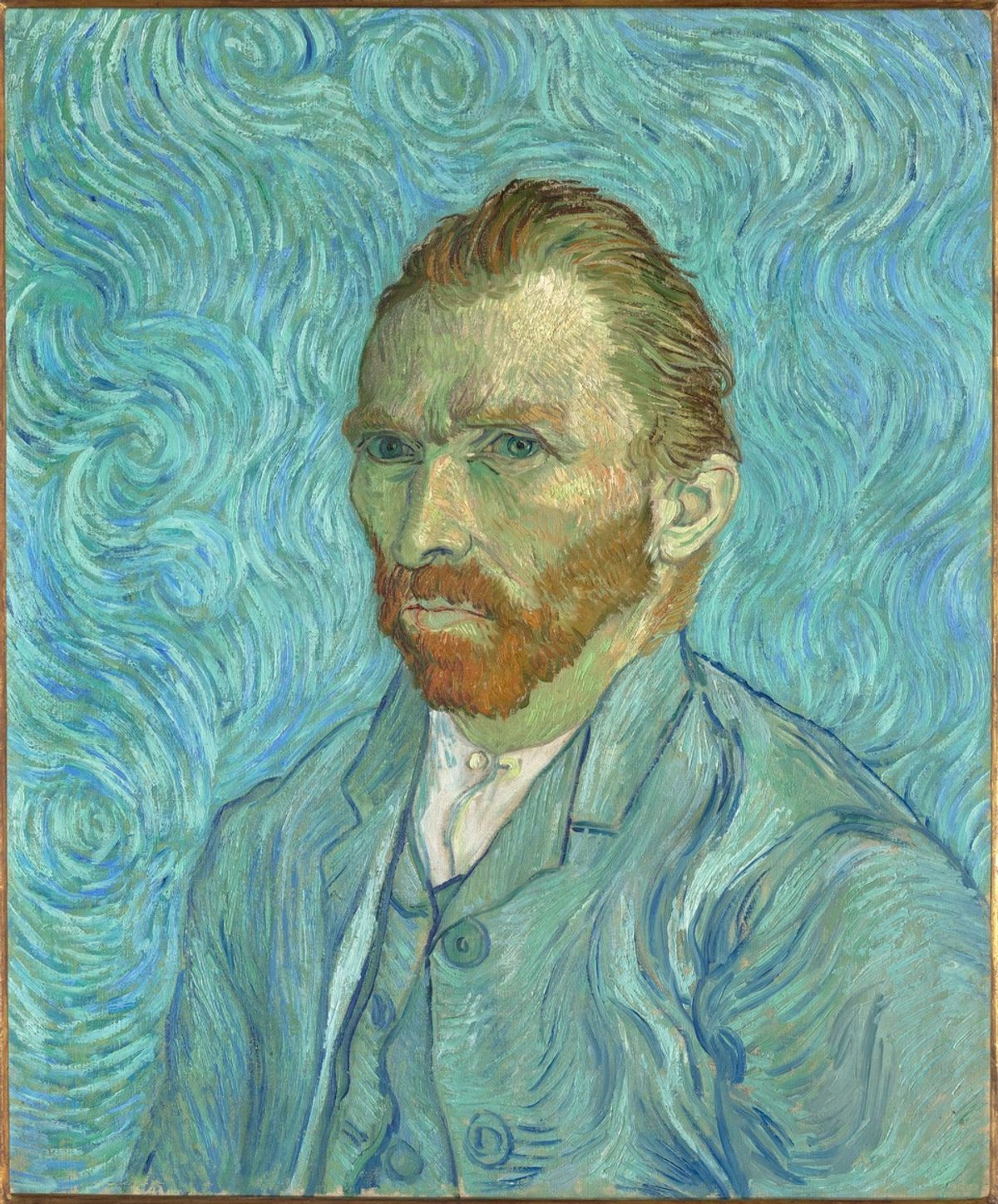

A few years ago, the question I was most often asked about Vincent van Gogh was, “Why did he cut off his ear?” Now it's, “Did he commit suicide, or was he actually murdered?”

The story of his extraordinary life has always excited just as much interest as his pathbreaking art.

The theory that Van Gogh’s death was murder (or manslaughter) first surfaced seriously in 2011, in a comprehensive biography by two American writers, Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith. They wrote that Van Gogh was shot in the abdomen on 27 July 1890 by 16-year-old René Secrétan, a summer visitor in Auvers-sur-Oise who taunted the artist. Van Gogh managed to stagger back to his inn, dying two days later from his wounds. The two authors based their theory on their imaginative interpretation of an interview that Secrétan gave in 1957, a few months before his death.

Naifeh and Smith argued that Van Gogh “welcomed death” and therefore the unexpected shooting. He then protected Secrétan by claiming it was suicide. The murder/manslaughter theory was subsequently taken up in different ways in two acclaimed films, the painted-animation Loving Vincent (2017) and artist Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate (2018).

However, I remain convinced that the traditional view that Van Gogh shot himself is correct; he was not killed by Secrétan. The murder story is yet another myth that has been added to those which have come to surround the artist. Here are ten reasons why it was suicide:

1. Vincent’s doctor believed it was suicide

A few hours after the shooting, Vincent’s doctor, Paul Gachet, wrote to the artist’s brother, Theo van Gogh, to break the news that “he has wounded himself”. Dr Gachet had inspected the wound and spoken with Vincent. Had there been anything to suggest possible foul play, he would presumably not have let the matter rest. Two weeks after Vincent’s death, he wrote again to Theo, explicitly using the word “suicide”.

Theo van Gogh (1889) © Van Gogh Museum archive, Amsterdam (b4781 V/1962)

2. Theo believed it was suicide

Theo, who rushed to his brother’s bedside and conversed with him during his final 12 hours, was convinced it was suicide. Three days after Vincent’s death, he wrote an emotionally charged letter to his wife, Jo: “One of his last words was: this is how I wanted to go & it took a few moments & then it was over & he found the peace he hadn’t been able to find on earth.” Had Theo any reason to believe his beloved brother might have been shot by someone else, he would surely have informed the police.

Emile Bernard, Self-portrait given to Van Gogh (1888) © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

3. Friends believed it was suicide

Emile Bernard, Van Gogh’s closest friend, attended the funeral and spoke with Dr Gachet and Theo. Dr Gachet told Bernard that he had hoped to save his patient’s life, but Vincent had warned him that “then I’ll have to do it over again”. Two days after the funeral, Bernard wrote a detailed account to the critic Albert Aurier: “He killed himself. On Sunday evening he went into the countryside around Auvers, placed his easel against a haystack and went behind the château and fired a revolver shot at himself.” Vincent had “done it in complete lucidity”, with a “wish to die”.

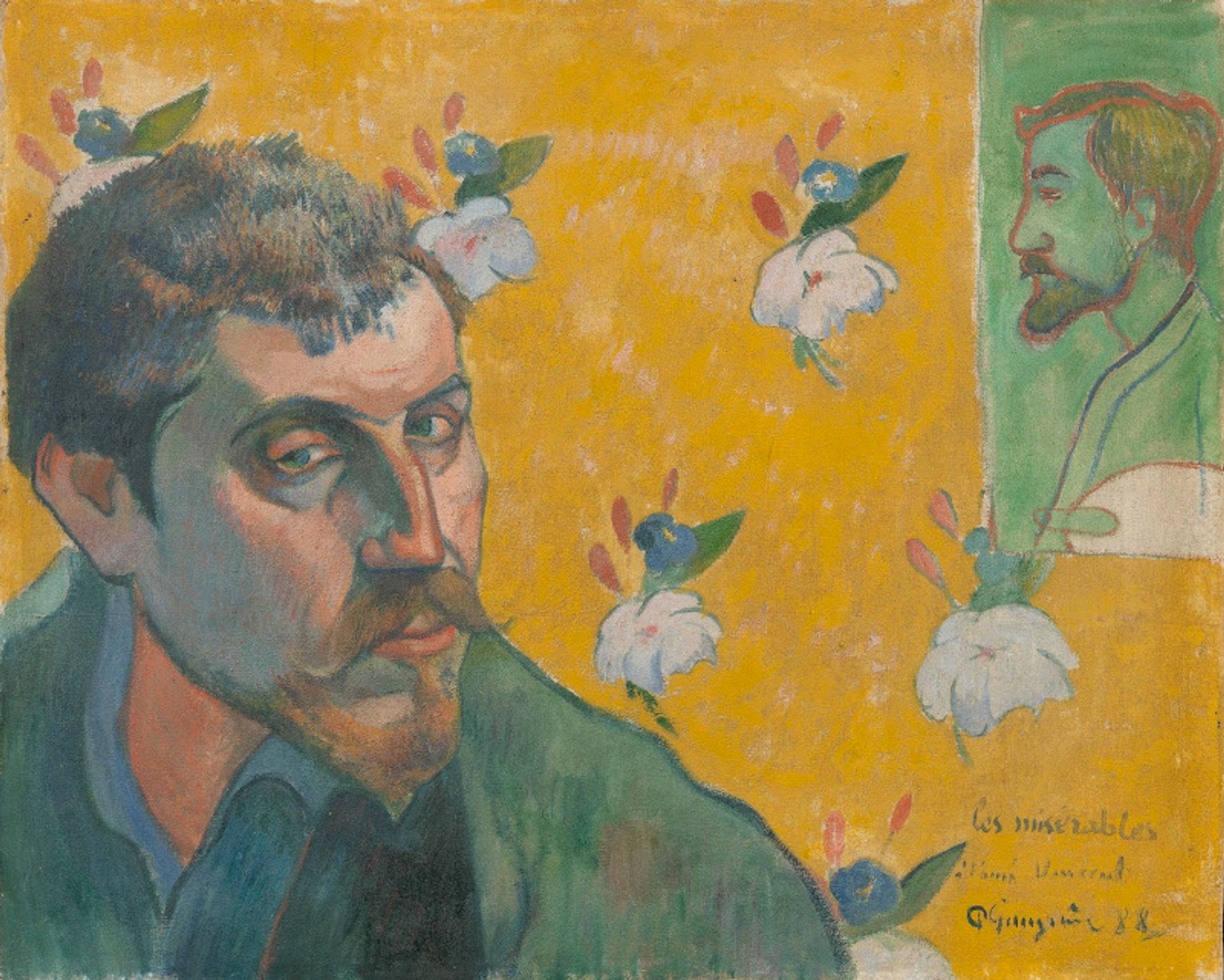

Paul Gauguin, Self-portrait given to Van Gogh (1888) © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

4. Paul Gauguin believed it was suicide

In Gauguin’s memoir, Avant et Après, he wrote that “Van Gogh shot himself in the stomach”. Although Gauguin was in Brittany at the time, he remained in touch with Vincent’s circle of friends. Gauguin knew Van Gogh well from their time together in the Yellow House in Arles, where their collaboration had come to an abrupt end with the ear incident, and he was only too aware of his friend’s fragile mental condition.

5. The police believed it was suicide

No police records about the shooting survive, but Bernard also informed Aurier that the innkeeper, Arthur Ravoux, had told him about “the gendarmes who came to his bed to reproach him for an act for which he was responsible”. His daughter, Adeline Ravoux (who was 13 at the time of the incident), later reported that her father had often spoken about Van Gogh. The artist had told the police: “What I have done is nobody else’s business. I am free to do what I like with my own body.” Surely the police would have followed up if they had harboured any suspicions of foul play. Adeline even named one of the gendarmes as Rigaumont. Although her testimony was given in the 1950s, more than 60 years after the events, subsequent research revealed that an Emile Rigaumont had indeed once served as a gendarme in the neighbouring village of Méry-sur-Oise.

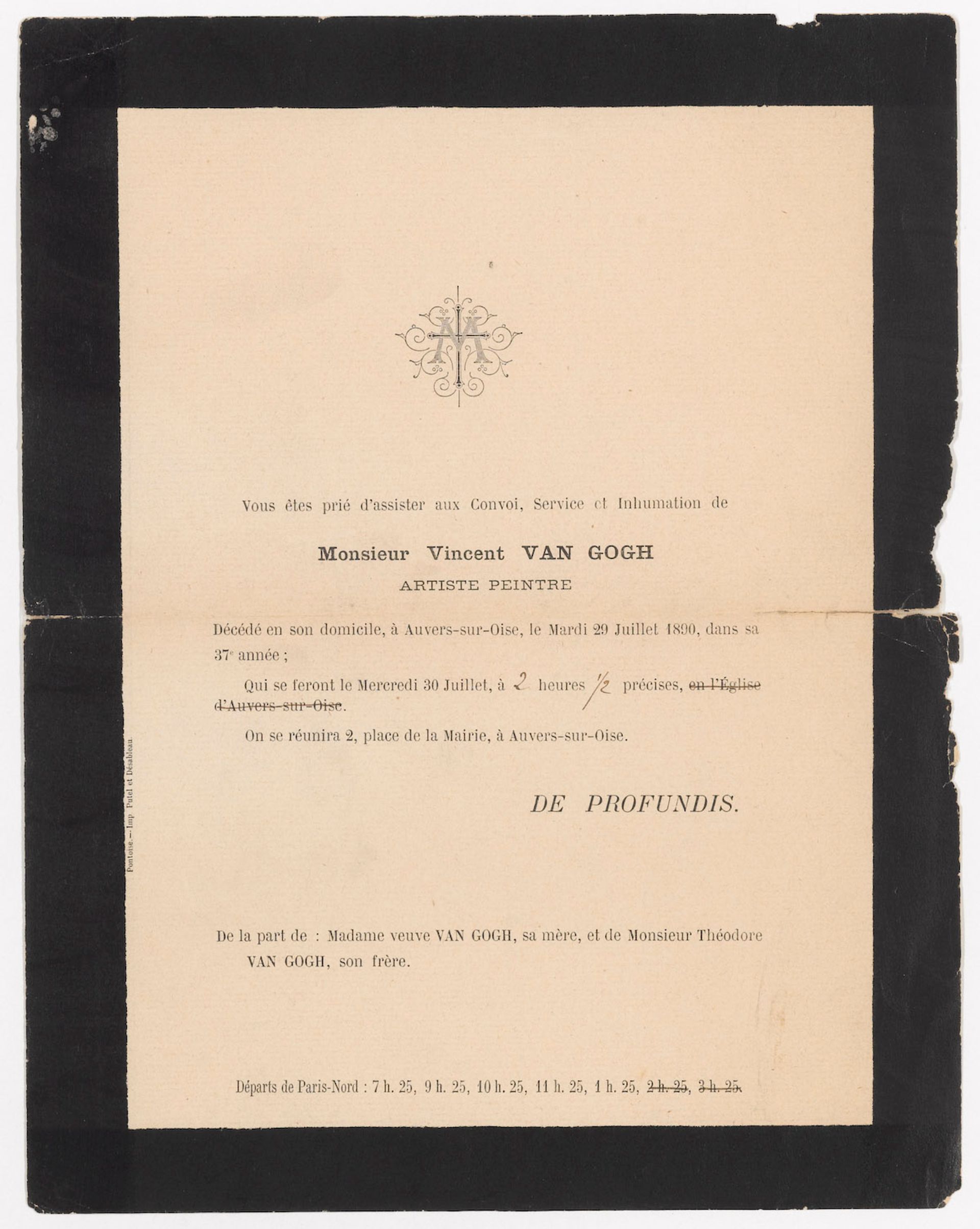

Notice of Vincent van Gogh’s funeral at Auvers-sur-Oise, 30 July 1890, with the church venue crossed out after the priest objected © Van Gogh Museum archive (b1993 V/1980)

6. The church believed it was suicide

Henri Tessier, the Catholic priest in Auvers, refused to allow the funeral service to be held in his church, or to provide the parish hearse to carry Van Gogh’s body to the cemetery. Tessier was presumably concerned that the Protestant artist had sinned by committing suicide. Theo then needed to amend the printed funeral invitations.

7. Vincent had tried to kill himself the year before

In April 1889, four months after mutilating his ear, Vincent had written to Theo: “If I was without your friendship I would be sent back without remorse to suicide, and however cowardly I am, I would end up going there.” A few months later he tried to poison himself by eating his paints and turpentine, but fortunately his doctor saved him. A few days after his recovery, Dr Théophile Peyron told Theo that Vincent’s “ideas of suicide have disappeared”. Vincent himself reported that “I’m trying to get better now like someone who, having wanted to commit suicide, finding the water too cold, tries to catch hold of the bank again”. He was undoubtedly a vulnerable individual.

8. Vincent faced a difficult time in the final months of his life

In May 1890, after a year in the asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Vincent moved north, to the village of Auvers. Throughout his career Theo had been his closest confidante and had provided a regular financial allowance. But Theo, an art dealer in Paris, had recently married and then had a son in January 1890. Vincent was therefore concerned that a wife and an infant would mean he might lose much of his brother’s emotional and financial support. He was also worried about Theo’s recent problems at work with the owners of the gallery. Although most of the time Vincent could cope with the challenges of his life, he was upset. Something pushed him over the edge in the afternoon of 27 July—presumably a recurrence of the mental condition that had suddenly led him to cut off most of his left ear in the Yellow House.

René Secrétan, aged 80, reproduced in Aesculape, March 1957

9. René Secrétan, the purported killer, never confessed and indeed claimed he had left Auvers before the shooting

The only occasion on which Secrétan publicly spoke about Van Gogh was in an interview published in the journal Aesculape in 1957, when he was aged 82. This was just a few months before his death. Secrétan never said he fired the shot, instead saying Vincent had somehow got hold of a gun, which had been in the young man's possession. Secrétan also had an apparent alibi, since he claimed to have left Auvers some days before the shooting. Although there is no way of verifying his statements, in my mind there is nothing in the interview which represents prima facie evidence that he might have been guilty of murder or manslaughter. In any case, it must be extremely rare for a victim fatally injured in a shooting by someone else to claim it was actually a suicide attempt. To add to the implausibility, why should Secrétan, if guilty, have voluntarily given an interview about Van Gogh nearly 70 years afterwards, at a time when he was under no suspicion?

Lefaucheux revolver which probably killed Van Gogh, sold by AuctionArt Rémy le Fur & Associés, Paris on 19 June 2019 © Martin Bailey

10. The recent emergence of the gun is further evidence for suicide

The corroded gun that is said to have killed Van Gogh was displayed and auctioned in Paris in June, fetching €162,500. It had been found in around 1960 by a farmer, abandoned in a field in the area where the artist is believed to have suffered the wound. If it is the Van Gogh gun, which is very likely (although not certain), then its discovery near the surface of the ground suggests it was abandoned rather than hidden. And if it was Secrétan who had fired the fatal shot, then surely he would have hidden the weapon properly—perhaps by burying it more deeply, or throwing it in the nearby River Oise. But if Van Gogh had pulled the trigger, he would have immediately fallen, dropping the gun.

In conclusion, all the key people at the time believed Van Gogh had shot himself. Suicide was then condemned by the Catholic church and regarded by society as wrong. Had Vincent’s family and friends had any suspicions that someone else was responsible, they surely would have voiced their concerns. And why point the finger at Secrétan? The only substantive information on his links with Van Gogh comes from his 1957 interview, in which he said nothing to suggest he was guilty of murder.

What would be useful in determining whether it was suicide or murder would be forensic evidence about the nature of the wound, but there is little information. Dr Gachet, who died in 1909, never spoke out about the wound during his lifetime, and the descriptions given after his death by his son were very brief (on the colour of the skin on the adjacent skin, its location on the body and the angle of the shot)—and these details have recently been subject to different interpretations.

We therefore have to make a judgement on what seems the more likely explanation. Should we accept Van Gogh’s words that he had decided to end his life? Or does Secrétan’s interview suggest it was he who pulled the trigger? For me, the answer is clear. As Theo put it so poignantly, Vincent’s then “found the peace he hadn’t been able to find on earth”.

- For a detailed explanation of the Naifeh and Smith theory, see their comprehensive book Van Gogh: The Life (Profile Books, 2011), particularly the appendix on Vincent’s fatal wounding, pp. 869-85, and follow-up article in Vanity Fair, December 2014. Two Van Gogh Museum specialists, Louis van Tilborgh and Teio Meedendorp, later published a detailed critique of the murder theory in the Burlington Magazine, July 2013.

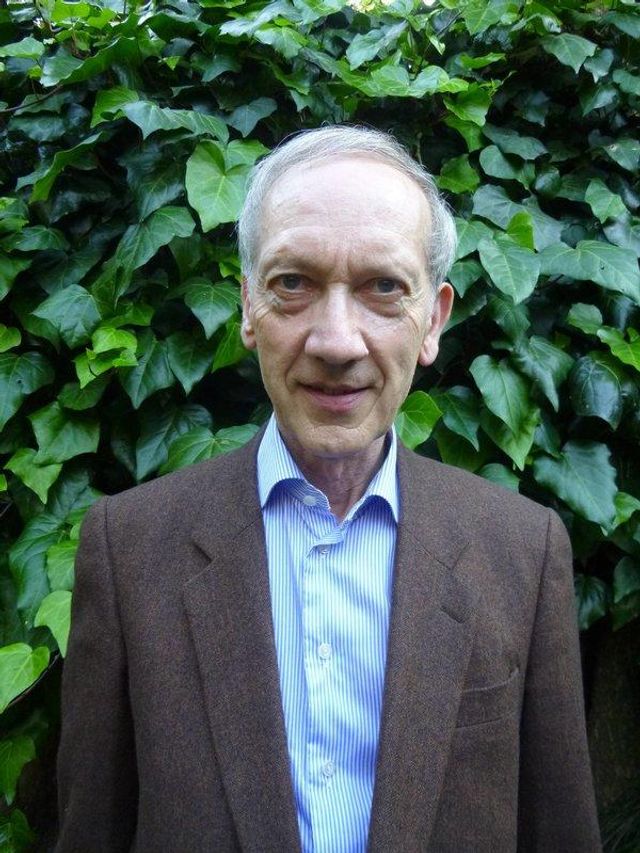

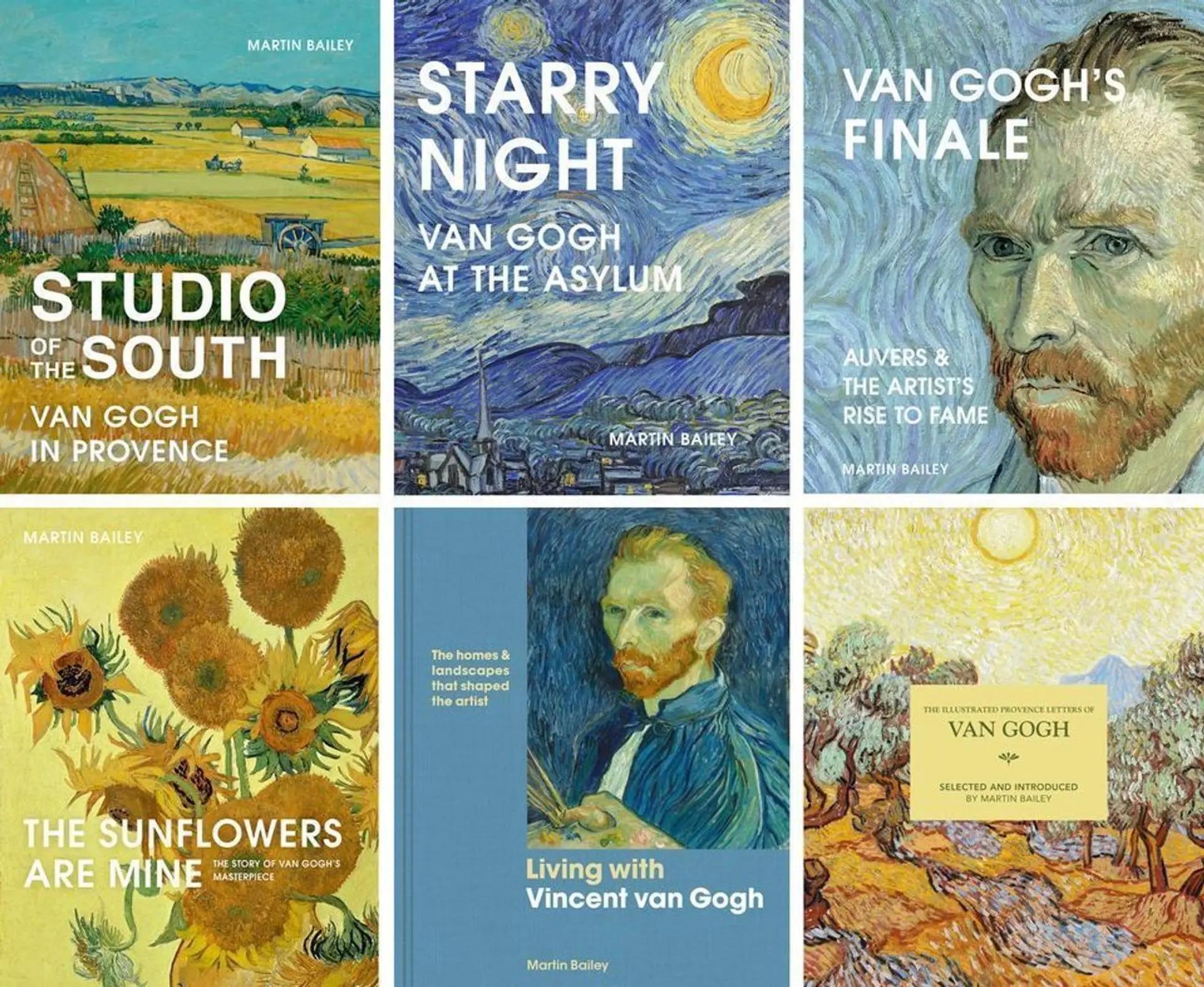

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). His latest book is Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: vangogh@theartnewspaper.com

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.