In May 1889 Van Gogh painted Irises, a close-up view of flowers in the garden of an asylum. He had come to this retreat on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence after mutilating his ear, following a row with Gauguin in the Yellow House in Arles.

On the day after his arrival, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo, saying that he already had two paintings “on the go”: one of a lilac bush and the other of “violet irises”. Irises is now among the greatest pictures in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Life at the asylum was very tedious for the inmates, with little to break the monotony. The appearance of an artist—especially one who was a foreigner—must have caused great excitement. “They all come to see when I’m working in the garden”, Vincent added in his letter.

After breakfast Van Gogh had immediately spotted some irises which had come into flower. Taking his easel, canvas and paints into the garden for the patients, he captured the transient beauty of their dramatic petals. One prominent white bloom is set among what originally was a sea of deep violet hues. Beneath the luscious flowers, the turquoise leaves form a marvellous swirling band.

Van Gogh’s Irises were indeed once violet, a colour he got by mixing blue and red pigments. But the red has has gradually faded, turning the flowers blue. So although the effect is still highly dramatic, it is not quite what the artist intended.

Irises were a favourite subject among Japanese artists, whose work Van Gogh greatly admired, and this almost certainly influenced his choice of subject. He owned prints by Utagawa Hiroshige, and may well have known his Horikiri Iris Garden (1850s). It is also possible that he knew Hokusai’s striking Irises and Grasshopper (late 1820s).

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Horikiri Iris Garden (1850s)

Working in the walled garden was Vincent’s one source of comfort and pleasure. Two weeks after his arrival he wrote to Theo, saying that “considering that life happens above all in the garden, it isn’t so sad”.

Exactly a year later Van Gogh again painted irises when they were at their best. This time he depicted them as cut flowers in a vase, echoing his Sunflower composition and setting them against a yellow background. One stem has just snapped and fallen, breaking the symmetry of the composition and serving as a reminder of life's transience.

Van Gogh’s Irises in a Vase (May 1890) © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Irises, the original painting done just after his arrival, was one of two pictures that Vincent offered for his first public exhibition—the annual show of hundreds of works organised by the Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris in September 1889. His other loan was Starry Night over the Rhône (October 1888), which is now at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

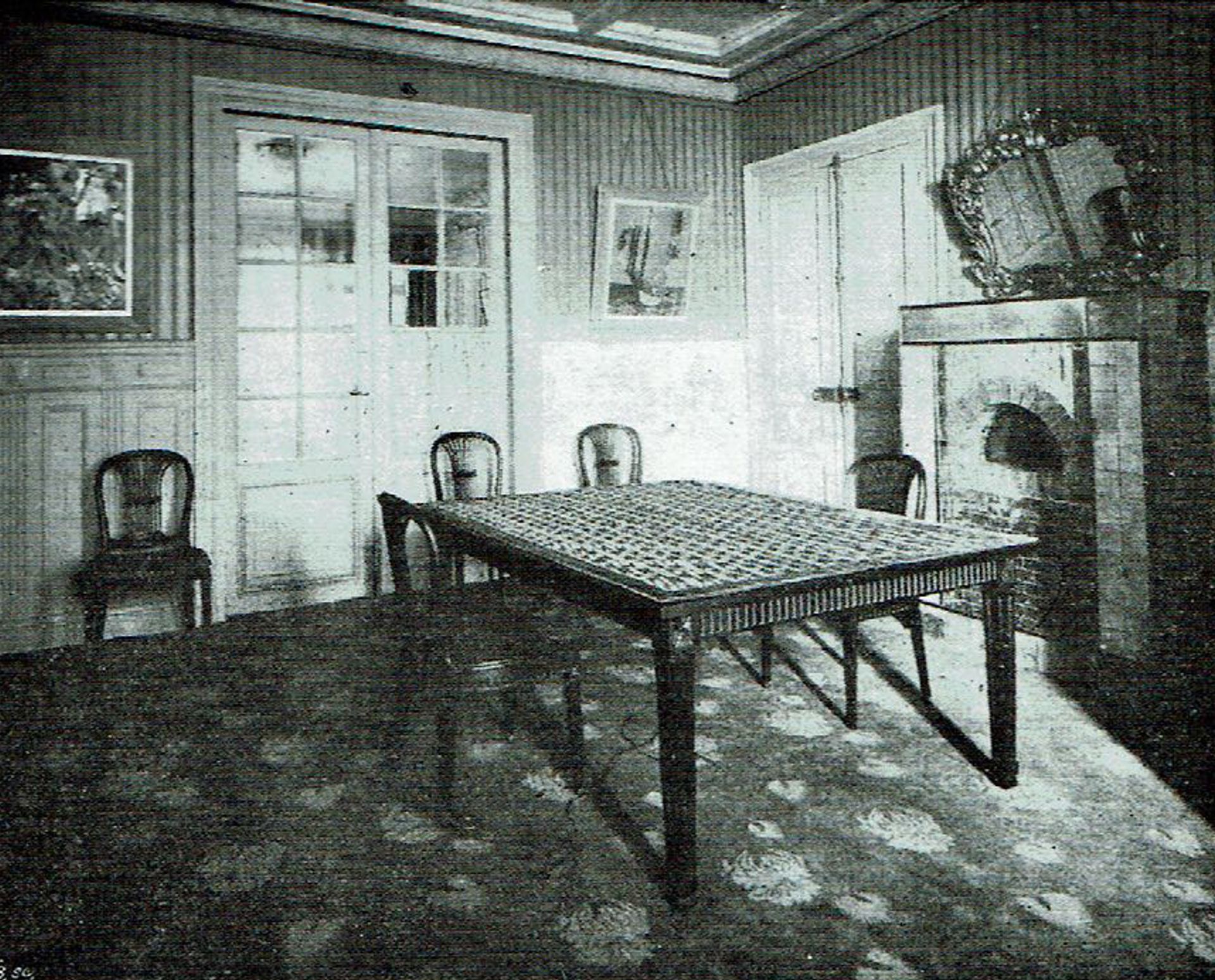

After Vincent’s death Irises and a version of Sunflowers (one with three blooms, now in a private collection) were probably his first paintings to be sold. In 1892, the pair was bought by the avant-garde critic Octave Mirbeau, who paid 600 francs (then £24). Fearing his wife would be furious with the expenditure, he told her they were a gift. An 1897 photograph shows the two paintings hanging in their dining room.

Octave Mirbeau’s dining room, with Irises hanging on the left © Revue Illustré, 1 January 1898

In 1925 Irises was bought by the Parisian couturier Jacques Doucet, a connoisseur of modern art and design. The next owner was the New York heiress Joan Payson, who paid $80,000 in 1947. Her heirs offered the painting at Sotheby’s in 1987, when it went for $54m, then a record price for an artwork at auction.

The successful bidder was the controversial Australian businessman Alan Bond, who a decade later would be imprisoned for fraud. After the 1987 auction it turned out that he did not have the money for Irises, so ownership of the Van Gogh was shared with Sotheby’s, which offered him a substantial loan. Bond failed to repay the loan and in 1990 the painting was sold privately to the J. Paul Getty Museum. Although the price remains confidential, it was probably close to the auction sum.

While Mirbeau had owned Irises and Sunflowers he had shown them to his friend Monet, who was on a visit from Giverny. Monet then responded: “How could a man who has loved flowers and light so much and has rendered them so well, how could he have managed to be so unhappy?”

Other Van Gogh news:

• Van Gogh’s Le Pont de Trinquetaille (June 1888) sold at Christie’s, New York on 13 May for $37.4m (including fees). The hammer price was $34m, almost at the top of the high estimate ($25m-$35m).

Van Gogh’s Le Pont de Trinquetaille (June 1888) © Christie's Images Ltd 2021

• Emilie Gordenker, the director of Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, is among dozens of Dutch museum directors who have signed a letter opposing the government’s plan to require museum visitors to produce test results showing they are free of Covid-19. The directors argue that this would represent “a barrier” for visitors. On 12 May the Dutch parliament approved the requirement for three months, although it rejected the proposed €7.50 testing charge. Dutch museums remain closed and no reopening date has been announced.

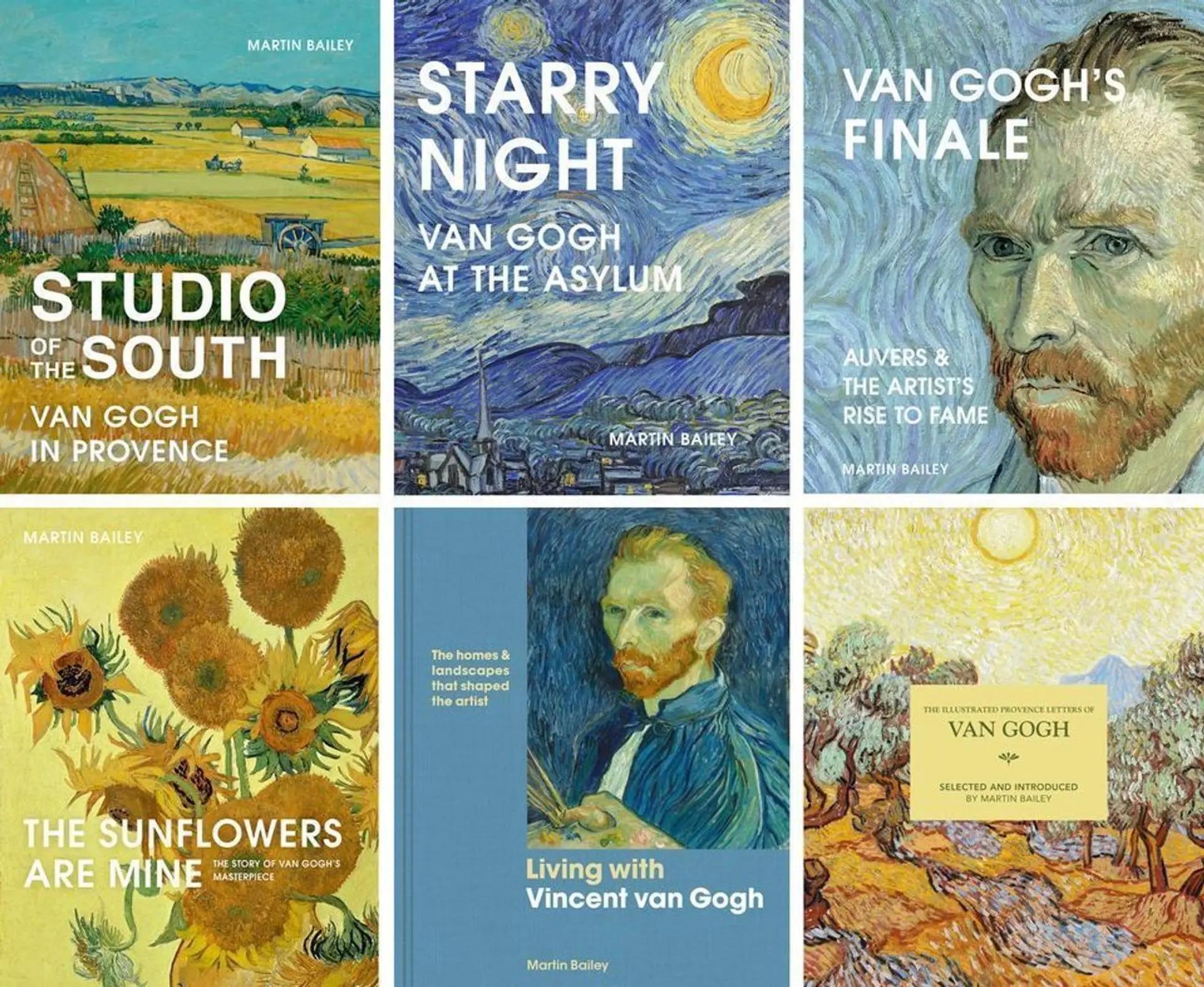

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. His latest publication is the reissued book The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: vangogh@theartnewspaper.com Please kindly refer queries about authentication of possible Van Goghs to the Van Gogh Museum.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.