Artists are often highly distinctive dressers but, according to Charlie Porter, their choice of clothes reveals much more than their sense of style. In his new book, What Artists Wear, the fashion critic offers a journey through the sartorial choices of Modern and contemporary artists, from Andy Warhol’s signature denim to the kaleidoscopic costumes of Yayoi Kusama, from the suits of Gilbert & George to the functional attire of Barbara Hepworth and casual wear of Martine Syms. Porter explains how, in the hands and on the backs of artists, garments can become potent tools of expression in their own right. Porter explains how what artists wear, whether at work or at play, can offer new insights into their processes, their lives and their work, as well as encouraging all of us to look long and hard at our own wardrobe choices.

Charlie Porter, the author of What Artists Wear © Richard Porter

“I had a very specific rule that Picasso would get just one line [in the book]”Charlie Porter

The Art Newspaper: What inspired you to write What Artists Wear?

Charlie Porter: The trigger was a piece I wrote for the Financial Times in 2015 when the Agnes Martin show was on at Tate Modern. I was absolutely captivated by a photo of Martin in her studio in 1960. She was wearing this very rudimentary, functional, quilted clothing, off-white, with diamond quilting—a top and a bottom. It was the garments themselves that I found so compelling. They looked so extraordinarily contemporary.

At the time, I was writing about catwalk shows where the garments had only been made to wear once and no one had lived in them. But it became more and more clear to me that there were many more interesting things to say about clothing rather than just up to the point of production.

From Georgia O’Keeffe’s suits to David Hockney’s colour blocking, you look at the way artists engage with, and play with, various kinds of assumptions and stereotypes.

We are deep into a time where artists put themselves in their work in many different ways, whether overtly like Cindy Sherman, or like Helen Cammock, who might walk across the screen in a shot to rearrange the camera but still be consciously present. Most of us dress for the work that we do, but given the way that artists work, they’re more likely not to have to follow any rules and so they dress much more instinctively, and much more directly connected to how they see themselves within society.

By looking at artists, you can look at the role of clothing within society and how it sends messages of power, of class, of race and of gender, and how artists subvert this, or try and go counter to it, or try and find workwear in which they can just function as human beings–like Agnes Martin, for example.

Barbara Hepworth photographed in St Ives in 1957 Photo: Paul Popper/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

Your book is not just about what artists wear, but also about how they wear their clothes. I like that you have a whole chapter called Paint on Clothing.

I loved doing that chapter because what it reveals is the physicality of work and what it takes for an artist to make that work. Anne Truitt is an amazing example of this: mixing her own paint and pigments in making these extraordinary sculptures that have one or two colour fields. She wanted to release colour and give it life, and she saw herself as if she was colour as well. The result was these extraordinarily messy clothes and this extraordinarily messy studio. By looking at this one jacket her daughter has still got, and the paint on the jacket, you can understand the labour it took her to make the art happen. You can see the same with Phyllida Barlow: the extraordinary labour and the hands-on-ness that it takes to make that work exist.

You also introduce a number of lesser known figures, such as the US performance artist Lynn Hershman Leeson and the Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh.

I wanted to spend more time with some of these figures who haven’t had a spotlight on them. I had a very specific rule that Picasso would get just one line, for example; that’s enough. It set a bar and meant that others could come through.

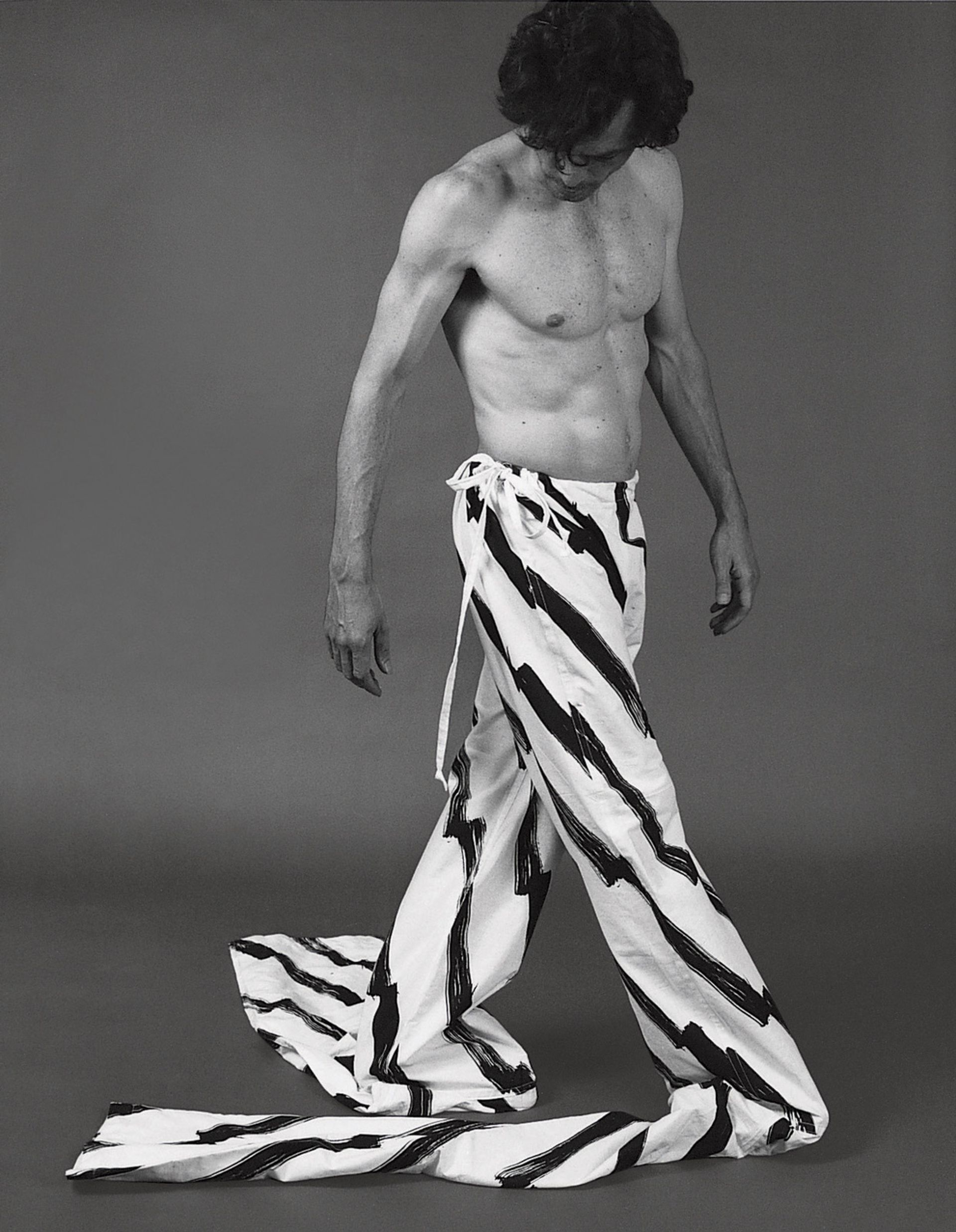

Richard Tuttle’s Pants (1979), created with the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia Photo: Will Brown, Collection of the Fabric Workshop and Museum

You begin the book with tailoring and end with casual wear—both culturally loaded ways of dressing.

Hopefully, there’s some sense of liberation that happens when you follow this arc from the one to the other. If you wear a suit, you are engaging in this language of white male power, and that’s for people who wear suits to think about. Why is it that the suit, which is absolutely a male garment, is the uniform of power? But also casual is very problematic in the sense of how it’s been co-opted by luxury fashion from working-class people of colour who have no finance but all this incredible style-signifying knowledge.

Martine Syms and Sondra Perry talk about that so eloquently. The book ends in this tense, agitated state that art is in at the moment, with artists trying to break free from institutions or breaking out of what they’re expected to do. We end with the 2019 Turner prize, where the four artists decide to ask to be a collective, so it’s ending in this place of agitation, using casual clothing to infiltrate and subvert society.

Gilbert & George wear their trademark suits in Philip Haas’s film The Singing Sculpture (1992) Photo: © Gilbert & George; Courtesy White Cube

You also round off the book with a clarion call to us all to examine not only the clothes of artists but also our own.

Sarah Lucas says that she wants the items of her own clothing that she uses in her work to stand in for her, as if she is directly there, in front of the viewer. And when you see another human, you also see yourself. If we’re looking at the way that artists wear clothes—to live, to subvert society or to try and change or radicalise society—we can also do the same. We can break free and start to question what it is we wear and why we wear it, and realise that there are all these hidden power languages of clothing.

• What Artists Wear, Charlie Porter, Penguin, 376pp, £14.99 (pb)