One of the most high-profile art censorship sagas of recent times is explored in a new book by Arnold Lehman out next month, titled Sensation: The Madonna, the Mayor, the Media, and the First Amendment. The former Brooklyn Museum director dives into the furore around the 1999 exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection, which took place at the New York museum while he was at the helm. The show had first opened at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1997 where it had also drawn protests and made headlines.

In New York, Chris Ofili’s painting The Holy Virgin Mary (1996)—depicting a black Madonna amidst porn magazine cut-outs and elephant dung—was at the centre of the storm. In response to the painting, which he called anti-Catholic, New York’s then-mayor Rudy Giuliani sought to cut the museum's funding and evict it from its city-owned building. “It has taken Lehman two decades to fully absorb and reflect on events, and this book… is his very personal account of what happened,” says the publisher in a statement. In the extract below, Lehman describes presenting the controversial works in Sensation to Giuliani and his cohorts at New York City Hall.

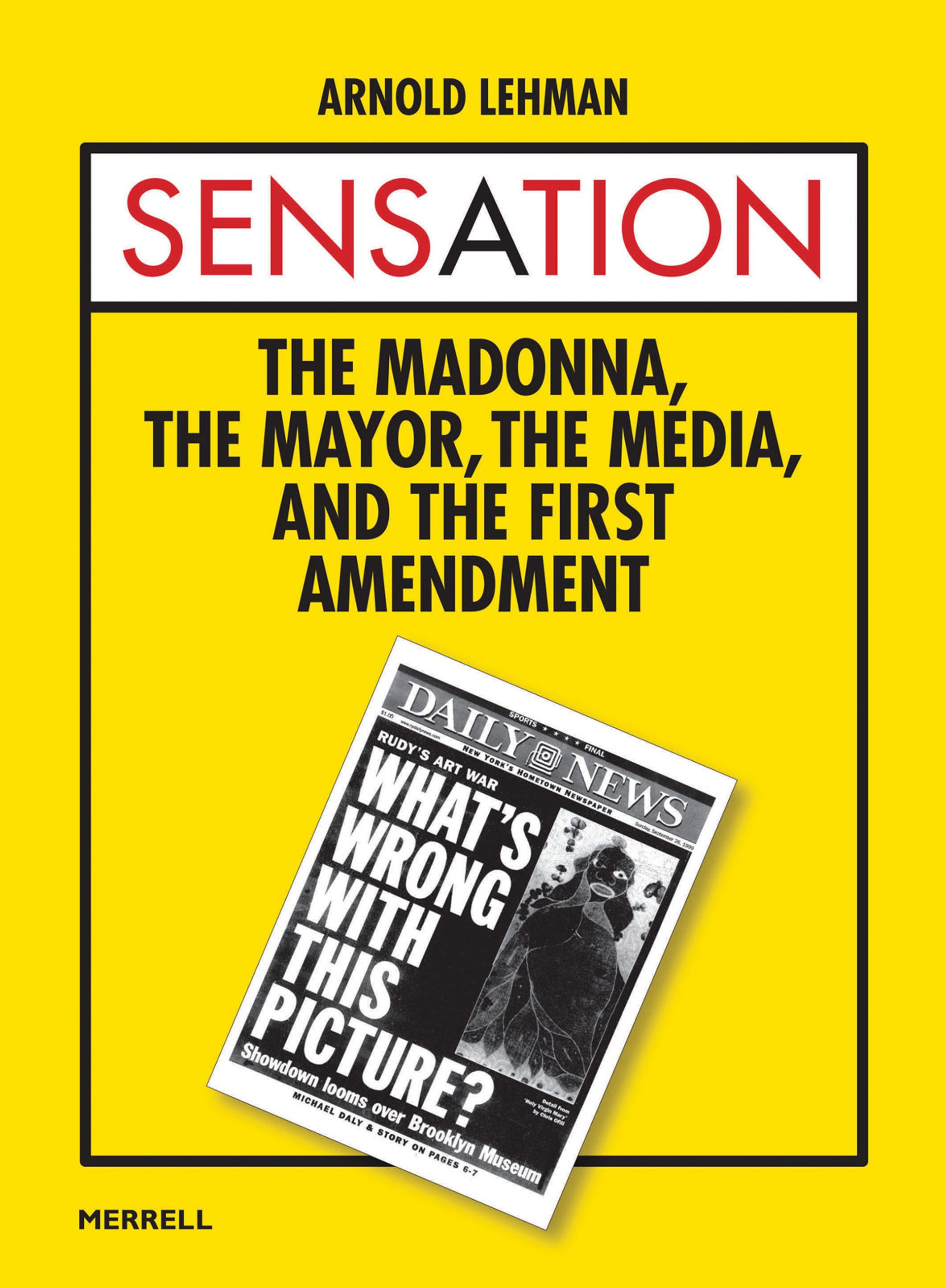

Sensation: The Madonna, the Mayor, the Media, and the First Amendment by Arnold Lehman

Extract from Sensation: The Madonna, the Mayor, the Media, and the First Amendment

Perhaps most surprising to me at the time, and certainly in retrospect, was the “Bastille Day meeting,” as I called it, with the mayor, in City Hall on July 14, 1999, a meeting that both our board chair, Bob Rubin, and I had requested on a number of occasions but with no response until we received a call a week before. With mayor Giuliani were DCA [Department of Cultural Affairs] commissioner Schuyler Chapin, deputy mayors Joseph Lhota and Randy Levine, and budget director Robert Harding. The mayor’s office had earlier that week indicated that we would have 15 minutes to present our capital funding request of $20m for Brooklyn Museum’s new front entrance. While the city had been providing operating funds for many decades to cultural organisations that were part of the CIGs—the Cultural Institutions Group, 33 organisations operating in city-owned buildings or on city-owned land, based on a formulaic annual allocation—capital funding was a hit-or-miss process most often dependent on political advocacy from the borough president, city council, mayor or some combination of those.

After a pleasant welcome, and before getting to talk about the museum’s pressing need for its proposed capital project, the mayor, Bob and I talked about Brooklyn, where both the mayor and I were born, and exchanged friendly jibes about his Yankees versus the Mets. I then used the first part of our slide presentation to show the major need for the new entrance as well as the highly engaging designs by our team of renowned Japanese architect Arata Isozaki and greatly respected New York architect James Polshek.

[…]

I concluded my presentation with slides from Sensation, starting with Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living—a ferocious shark encased in hundreds of gallons of formaldehyde. This immediately got the attention of everyone in the room and gave me the opportunity to talk about the exhibition generally, the necessary ticketed admission fees and, most importantly, its provocative nature. I showed one image after another of what we had understood to be the most controversial works in the exhibition as reported from the Royal Academy and the media. I prefaced this part of my presentation by saying that the RA’s distinguished Exhibitions Secretary for two decades, Norman Rosenthal, had personally selected the works for the Sensation exhibition from the premier contemporary art collection in Great Britain, that of Charles Saatchi.

Installation view of Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection at the Brooklyn Museum. The show opened in October 1999 and included works by artists such as Damien Hirst, Marcus Harvey and Sarah Lucas Photo: Brooklyn Museum

Again thinking that I would prepare Giuliani for what might happen, I went on to say that in the months before the exhibition opened to the public in London, there were already attacks in the British press and by Royal Academicians on the controversial nature of the works to be shown and that—trying to make the connection as clear as possible to the mayor—Rosenthal had been quoted in the UK Times in February 1997 [saying] that “such works were as shocking, difficult, and thought-provoking as Goya’s Disasters of War and Picasso’s Guernica had been in their day” and that “art is good when it perplexes us.” As I was quoting Rosenthal, I immediately thought that I might have overestimated the art-historical knowledge of the mayor and his lieutenants!

[…]

As the meeting was ending, Mayor Giuliani shook hands with Bob Rubin, patted me on the back, and told Deputy Mayor Randy Levine to “give them what they want—they’re good guys.” With that said, I was already banking that $20 million in city capital funding for the museum’s new entrance!

That was the last time I spoke with Rudy Giuliani.

[….]

However, on Wednesday morning, September 22, I answered a call from Schuyler to my office. After a few moments of nervous but cordial chitchat, he abruptly announced that he was delivering “a message from Mayor Giuliani that unless the museum immediately cancelled the Sensation exhibition, the city would terminate all funding for the BMA.” I was incredulous that he had agreed to deliver this preposterous message and remained silent on the phone. Schuyler asked nervously, “Arnold? Arnold, are you there?” I held my temper and spoke coolly, with great deliberation: “I’m here, Schuyler. But where are you in this ultimatum? Where are you in all of this? What about freedom of expression?”

“I’m just the messenger. I’m just the messenger,” Schuyler responded even more nervously. With my voice raised but still under control (which, thinking about it later, amazed me), I responded, “But you’re the damn commissioner of cultural affairs for the city of New York! You have to take a stand!” He hung up the phone. An hour later, he called again to tell me that the mayor’s position had not changed. I asked if he had spoken to Giuliani, but he didn’t answer. I asked if he was going to do something about this destructiveness on the part of the mayor?

“Like what?” he asked.

“Like quit,” I replied.

Schuyler said something I couldn’t make out, seeming almost to whimper in response to my now nearly shouted suggestion. This time, I hung up. Within minutes, Giuliani appeared for a City Hall press briefing, seemingly timed directly to Schuyler’s second warning. The New York Times reported that one of the mayor’s aides had prompted a CBS reporter at the briefing, Mary Gay Taylor, to ask a question about recent press coverage of Sensation. Giuliani jumped in with a clearly rehearsed answer denouncing the museum: “You don’t have a right to government subsidy for desecrating somebody else’s religion… and, therefore we will do everything that we can to remove funding for the Brooklyn Museum until the director comes to his senses and realises that if you are a government-subsidised enterprise, then you can’t do things that desecrate the most personal and deeply held views of people in society.” Needless to say, Giuliani’s message “until the director comes to his senses” rang louder in my ears than had I been standing in the belfry of London’s Big Ben.

• Sensation: The Madonna, the Mayor, the Media, and the First Amendment, Arnold Lehman, Merrell Publishers, 248pp, £25 (hb), published 2 September