The De Young Museum in San Francisco will open a major retrospective this month devoted to the pioneering artist Judy Chicago. The show chronicles more than six decades of her prolific career and aims to move beyond the common focus on her magnum opus, The Dinner Party (1974-79). The landmark feminist installation—made up of a banquet table covered with ceramic plates depicting vulvas honouring historic and mythological women—has somewhat overshadowed other facets of Chicago’s career, drawing both impassioned praise and criticism since it was first shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979.

The De Young’s show offers a “renewed appreciation for the grandeur of Chicago’s practice—her range, vision, techniques and immense output—with The Dinner Party incorporated into the broader narrative of her practice”, says Claudia Schmuckli, the curator of contemporary art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Decades before the work was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 2007, the piece was subject to “critical annihilation”, punctuated by “discrepancies between critical and popular reception to the work, a sentiment that has—more or less—reflected her entire career up until now, when the art world has become more receptive to her work”.

“Chicago was ahead of her time and thinking about toxic masculinity when that term didn’t exist,” Schmuckli adds, “and was thinking about gender before that concept had been theorised in academia.”

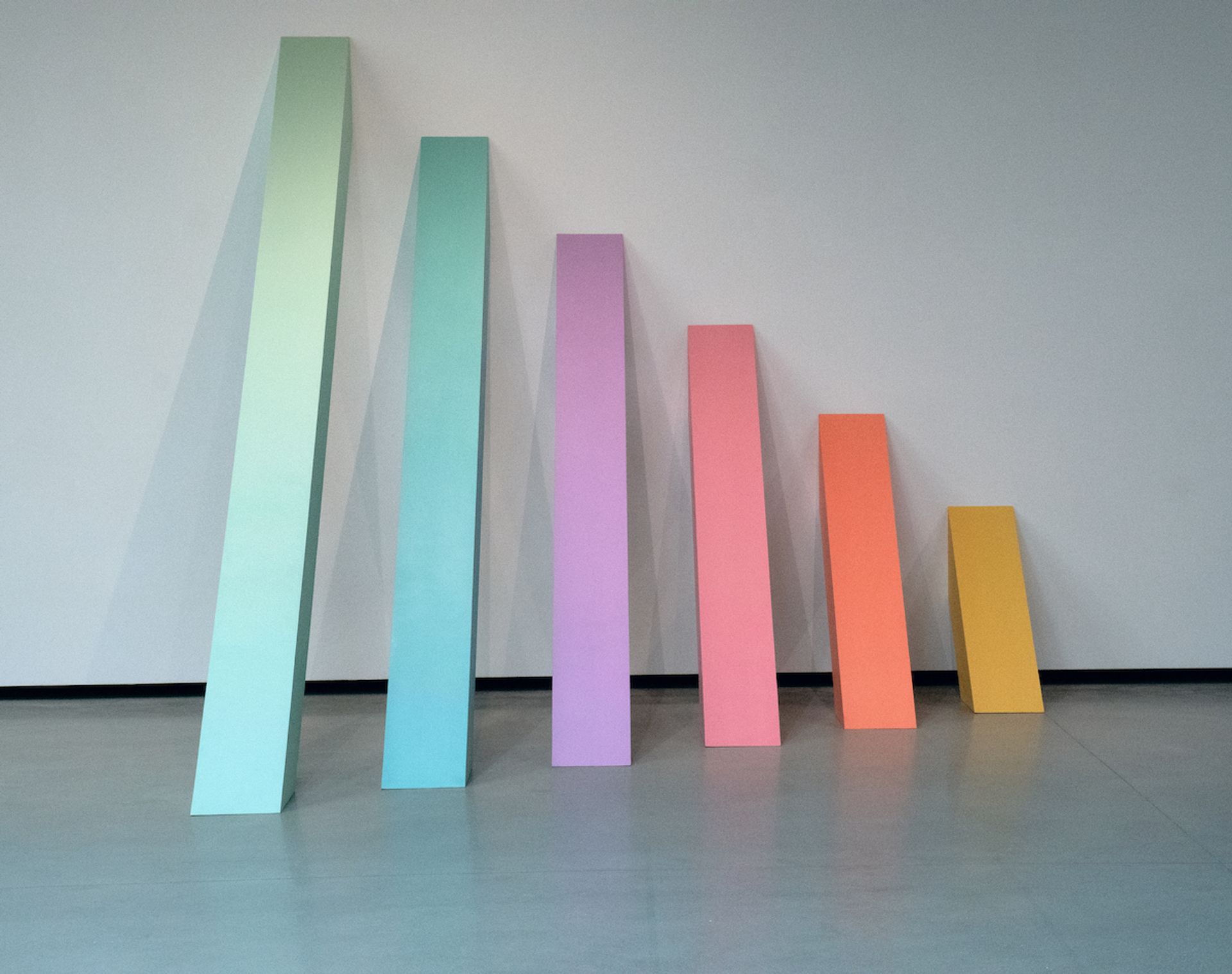

Around 125 paintings, drawings, ceramic sculptures, and prints by the artist are in the show, including several little-known bodies of work, such as Minimalist sculptures Chicago made in Los Angeles in the 1960s, which demonstrate her earliest investigations of the rainbow colour palette, and car hoods from the same period that she made while enrolled in auto-body school to expand her painting technique. Some of these works are juxtaposed with her signature psychedelic paintings made in the same vibrant palettes.

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Pickett (1965/2021) Collection of Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

There is also a section dedicated to Chicago’s role in advancing the second-wave feminist art movement, including rarely-seen ceramic “goddesses” and other works in which she explored the female visual lexicon.

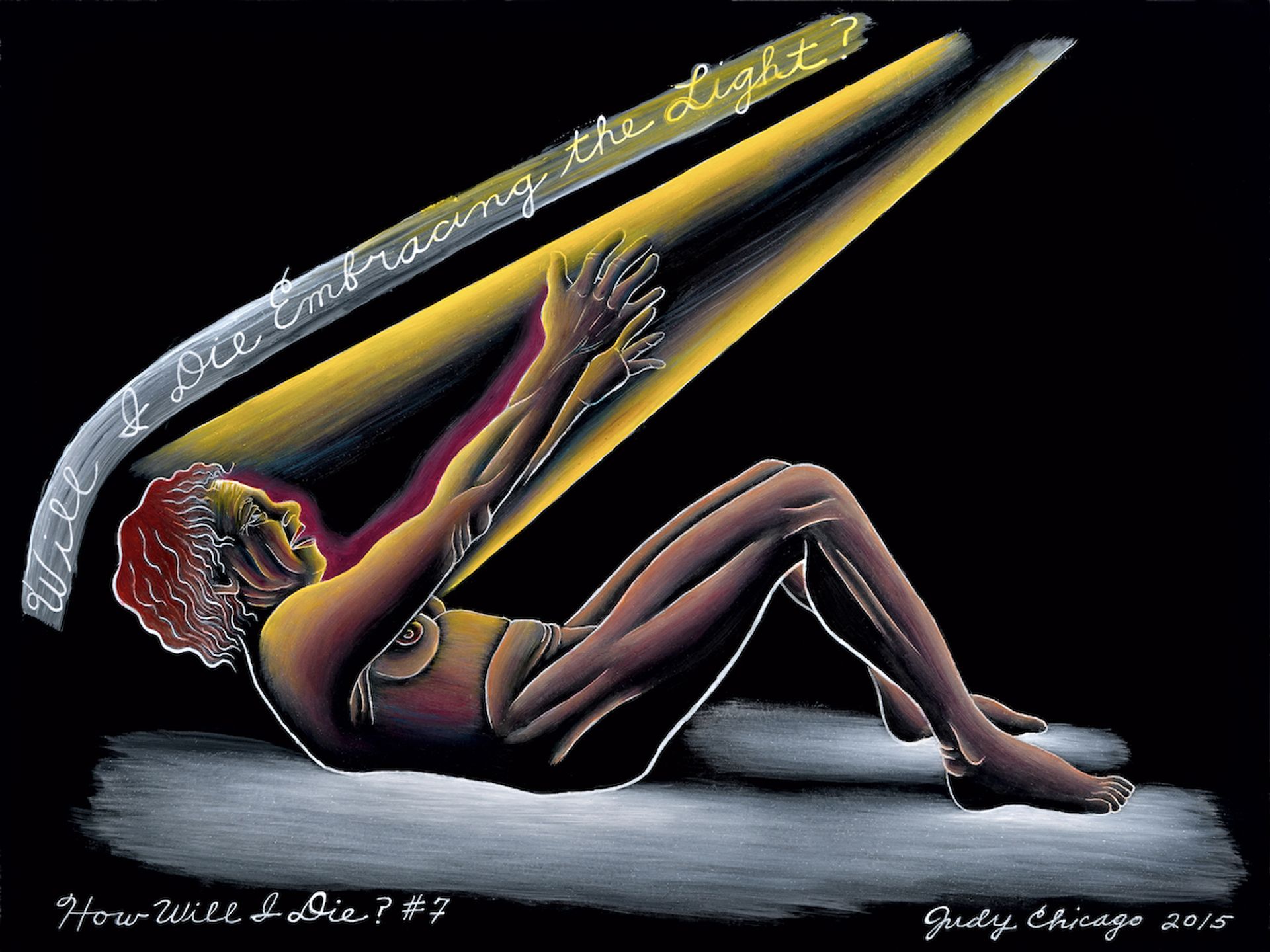

Works like the recent mixed-media sculptural series The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction, from 2015-16, reflect the artist’s meditations on impermanence and environmental concerns, and highlight how Chicago “has always been progressive in her thinking—not just in terms of fighting for equality for women but for all human and non-human entities”, Schmuckli says. The series also marks “the first time Chicago’s concerns and society’s concerns seem to have aligned”, the curator adds. “All the issues she’s been talking about for decades are now front and centre in our minds.”

Judy Chicago, How Will I Die #7, from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2015) Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; Jessica Silverman, San Francisco; Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles; and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe

Another section features rarely seen works in which Chicago explores her Jewish heritage. The evocative paintings on linen in the series The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985-93)—created while Chicago was also working on the series Power Play, which examines gender constructs—emphasise “the dominant or domineering side of masculine identity and patriarchal society—qualities that are taken to extremes within the constructs of societies, dictatorships and tyrannies,” Schmuckli says.

The show also includes archival films and photographs of Chicago’s Atmospheres series of site-specific performances, first presented in the California desert in the late 1960s, in which she sought to conceptually “feminise” the landscape through eruptions of coloured smoke. She has conceived a special iteration of the series for the show called Forever de Young (2021). The smoke sculpture—a successive release of pigments representing the full colour spectrum—will be staged on a pyramidal structure outside of the museum on 16 October.

While Chicago’s work over the years has been marked by variety and experimentation, Schmuckli says there is a “throughline in terms of adherence to colour and in seeking fusion between figure and ground, and how she treats materials, whether that is plexiglass, fabric, ceramics or glass”. The show highlights how, in each instance, Chicago has “developed new techniques or pushed the boundaries of existing techniques, and has remained consistent in her conceptual and technical approach to the work.”