In August 1888, Van Gogh painted four Sunflower still-lifes in the Yellow House in Arles. The last two are famous—the 14 flowers on a turquoise background (now in Munich) and the 15 flowers on a yellow background (in London).

Van Gogh’s Fourteen Sunflowers on a turquoise background (August 1888) and Fifteen Sunflowers on a yellow background (August 1888) Courtesy of Neue Pinakothek, Munich and National Gallery, London

But the first two are hardly known, other than by specialists. Van Gogh began his series with Three Sunflowers (August 1888), which he painted with a turquoise background. It has always been hidden away in private collections. The last time it was displayed was in a one-month exhibition at Cleveland Art Gallery in 1948, so very few people will now remember that show. Three Sunflowers was not even published in colour until the 1980s.

Van Gogh’s Three Sunflowers (August 1888) Private collection

Vincent succinctly described the picture to his brother Theo as “3 large flowers in a green vase, light background”. The sheer size of the flowers is dazzling, with the one on the left as large as the pot. He painted the flowers against a vibrant turquoise, quite different from his earlier still-lifes done in Paris when he mainly placed blooms on a dark background. In Arles, Van Gogh became very bold in his use of colour.

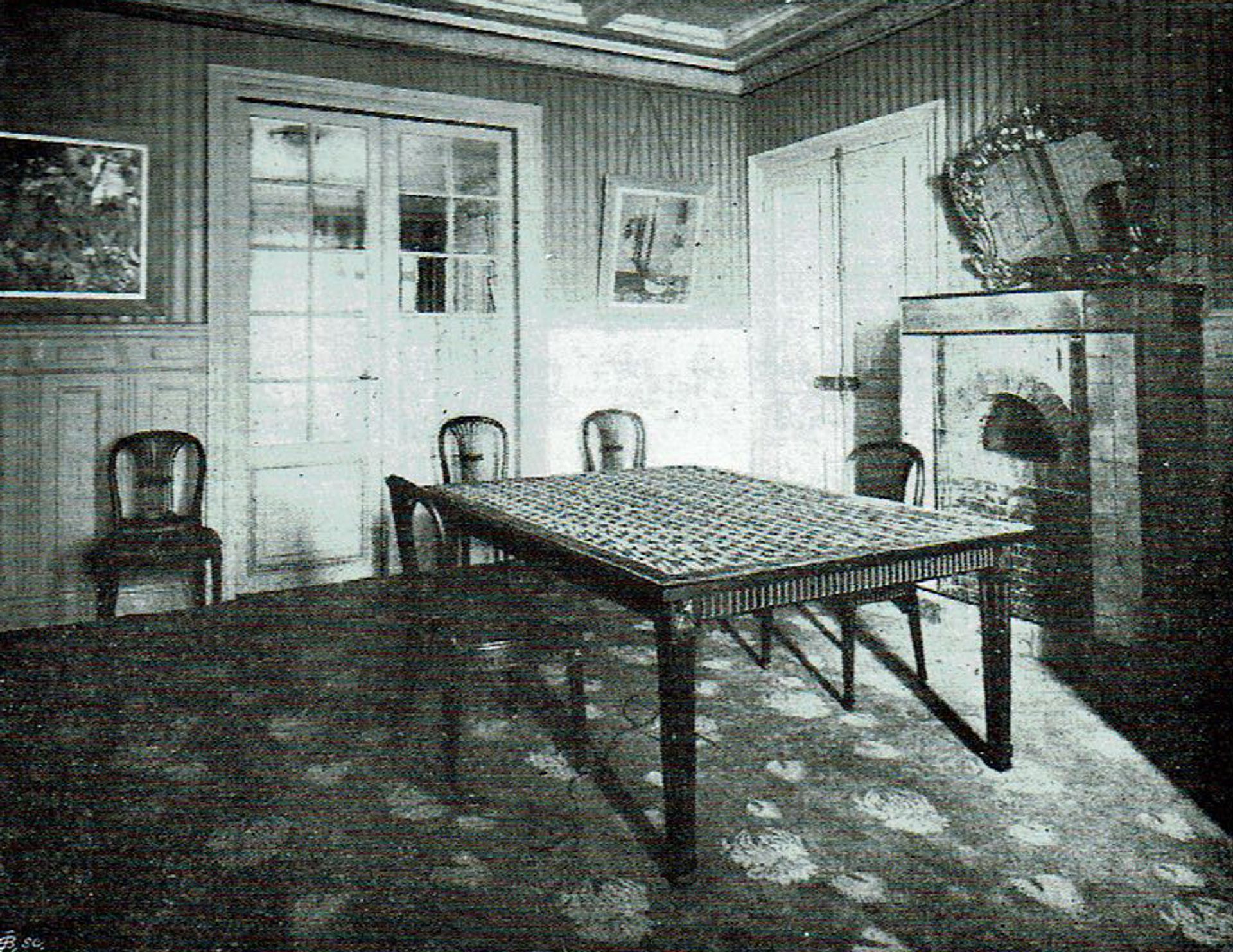

Three Sunflowers was probably one of the first two Van Gogh works to be sold after the artist’s death. Along with Irises (May 1889), it was bought in 1891 by the Parisian critic Octave Mirbeau, who paid £24 for the pair. One of the earliest photographs of Van Gogh paintings in a collector’s home shows Mirbeau’s dining room.

Octave Mirbeau’s dining room, with Three Sunflowers hanging in the middle and Irises on the left, published in Revue Illustré, 1 January 1898

The next owner was the Parisian couturier Jacques Doucet, a lover of modern art. He commissioned the Art Deco designer Pierre Legrain to create an extremely bold black lacquer frame for the painting (now sadly lost). Doucet’s heir sold Three Sunflowers in 1970 and it went to a Greek shipping magnate, who sold the Van Gogh work in the late 1990s.

In 1996, the painting was offered on sale to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, but the deal fell through. Instead it went to an unidentified private collector. When Three Sunflowers eventually surfaces on the market it will probably fetch a record sum for a Van Gogh painting.

Van Gogh’s Six Sunflowers (August 1888), destroyed in 1945

The other relatively unknown August 1888 still-life is Six Sunflowers. Once again Vincent’s description is low-key: “3 flowers, one flower that’s gone to seed and lost its petals and a bud on a royal blue background”. Compared with Three Sunflowers, probably painted just the day before, the blooms here are presented more schematically, emphasising their spiky leafs and sepals.

Six Sunflowers was the first Van Gogh to be bought by a Japanese collector. In 1920 it was acquired by Koyata Yamamoto, a wealthy cotton trader from Ashiya, near Osaka. He paid the equivalent of £3,200. Yamamoto then hung the painting above his sofa, in a very ornate gilded frame.

Koyata Yamamoto (left), with the writer Saneatsu Mushakoji, in his Ashiya home, 1938 Courtesy of Mushakoji Saneatsu Memorial Museum, Chofu, Tokyo

On 6 August 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Ashiya was devastated in a separate American attack. More than 1,500 conventional bombs were dropped on Ashiya, with fires quickly spreading. Yamamoto’s house was set alight and Six Sunflowers was engulfed in the flames. Yamamoto escaped the bombing, living until 1963.

Few of Van Gogh’s paintings were photographed in colour before the war, but fortunately Six Sunflowers was among them. A few years ago I made a discovery in an early Japanese publication. A very rare portfolio of four reproductions of Post-Impressionist art included a print of Six Sunflowers, which was in an orange surround. At first glance the orange border seemed to be something that had been added by the publisher.

Portfolio with prints of Six Sunflowers and three Cézannes, published by Shirakaba, Tokyo, 1921

I then went back to Van Gogh’s letters. Immediately after completing Six Sunflowers he had written to his fellow artist Emile Bernard: the yellows of the flowers would ”burst” against the blue background, “framed with thin laths painted in orange lead” (orange lead is a bright yellow-orange pigment). The effect, he said, would be of “stained-glass windows of a Gothic church”.

Vincent made (or ordered from a local carpenter) a simple narrow frame, probably of pine, which he then painted orange—to contrast with the deep blue of the painting. The complementary colours, he felt, would enhance the dramatic effect of the sunflowers.

It is tragic that Six Sunflowers was destroyed in the Second World War. But thanks to this recently rediscovered 1921 print, we can at least see the painting as Van Gogh intended.

Other Van Gogh news

• Raffaele Imperiale, alleged to be behind the theft of two Van Gogh paintings and involvement in drug trafficking, has been arrested in Dubai. The Italian authorities are now seeking his extradition. In 2002, View of the Sea at Scheveningen (1882) and Congregation leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen (1884-85) were stolen from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Both were recovered in 2016 in Naples, in a property linked to Imperiale. After conservation the pictures went back on display in April 2019.

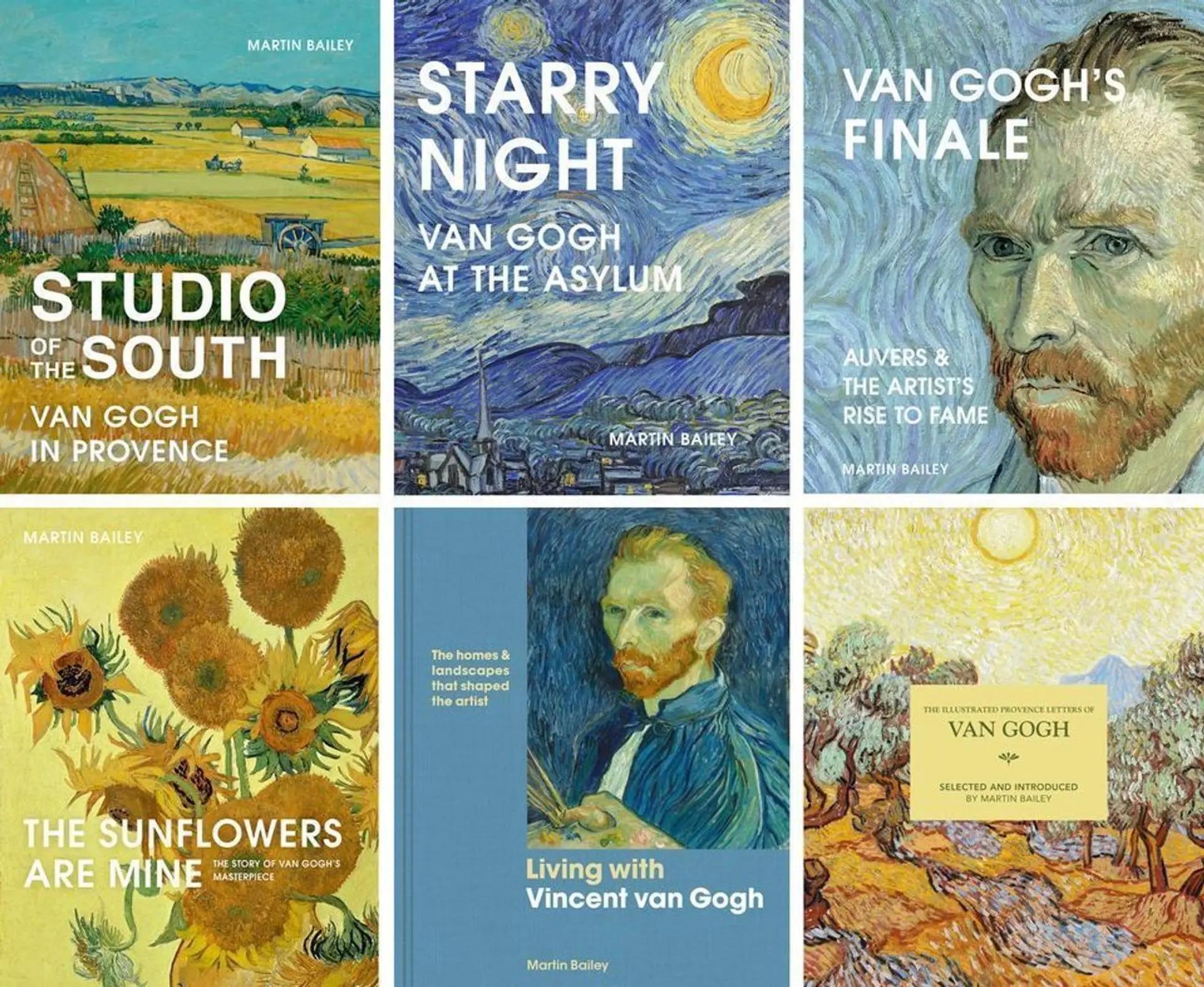

• For more about the Sunflowers, see my book The Sunflowers are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece, recently out in paperback.

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. His latest publication is the reissued book The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: vangogh@theartnewspaper.com Please kindly refer queries about authentication of possible Van Goghs to the Van Gogh Museum.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.