When the art world looks back on 2021, the story will be a mix of triumph and continued uncertainty. Coming out of a largely bleak 2020, which saw art fairs tumble and shutter after the first few months of the year, the artists, sellers and buyers that populate the US’s largest arts hub faced the pivot of a lifetime. How does the art business carry on when a global pandemic has stopped the whole world cold? How do we know when things have returned to normal? Can we at least raise a glass since we have made it this far?

Way back in 2019—try hard to picture it; time moves differently now in the post-pandemic world—events were the driving force behind the art market. That year alone, the art world calendar boasted upwards of 178 art fairs, with at least one major international fair every fiscal quarter. Then there were the 27 biennials and triennials peppered throughout the years. In the matter of a month or two, as Covid-19 spread across borders, all that impetus and market energy dissipated, like so much disinfectant spray in the wind. But the art world proved to be elastic. The key to survival in 2020 was also the key to success as the industry attempted to return to normal this year: embracing technology and a certain lightness of foot. The once cobbled-together online viewing rooms (OVRs) and livestreamed auctions have become sleeker. And more importantly, there has been a willingness to embrace both the chaos the pandemic brought to the once carved-in-stone calendar and the market’s “bring the buyers what they want when they want it” mentality.

During the press conference that followed the 20th Century and Contemporary Art evening sale at Phillips on 23 June, Edward Dolman, then the chief executive, said the pandemic “detonated the traditional sales calendar”, but that in the long run it did not matter. “We know our international clients now will buy great works they see, properly estimated and presented, at whatever time of year we present them,” he said. A survey of market insiders by the analyst firm ArtTactic released in July suggests he is right. Confidence in the art market is at its highest since 2014, up 89% from an all-time low in May 2020. That confidence makes sense considering auction sales saw an increase of 230% for the first half of 2021, according to the London-based data analytics company Pi-eX, which found that sales from the triumvirate of international auction houses—Christie’s, Phillips and Sotheby’s—brought in a combined $5.8bn by the end of June, $4bn more than in 2020.

Last year’s Armory Show in March was the last in-person art event many in New York attended before the pandemic set in. The fair moved to September this year and could serve as a bellwether for how the art industry will handle the Delta variant Photo: Teddy Wolff. Courtesy of The Armory Show

Of course, if you really want to know whether the art world has begun to normalise, glance at your diary. How much free time do you have? Last year, the answer was likely: “Far too much. I’ve done every Van Gogh colouring book Amazon has to offer and I’ve finished watching Netflix. All of it.” But with Frieze New York successfully bringing the in-person art fair back in May, suddenly the art world we once knew seemed back within reach. Similarly, the Armory Show, held this year in September rather than its usual March (which made it the last in-person art event many in New York attended before the pandemic truly set in), is poised to be the first major event of the autumn season, serving as a bellwether for how the arts industry will handle Delta and other Covid-19 variants.

But is a return to business as usual really what the industry wants? Juggling 200 events per year, not including the regular museum and gallery openings, galas, art weekends and the occasional non-work-related social call seems excessive—even in a field where nine-figure price tags are not uncommon and curators can make names for themselves speaking for 24 hours straight. It even feels unnecessary, given that in May 2020, US galleries projected a 73% loss in revenue. As it turned out, however, 49% surpassed their revenue expectations for the first half of 2021, and 65% said they planned on increasing their artist roster, according to a recent survey of 81 galleries by the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA). One gallerist told The Art Newspaper it would be very surprising if the more well-established galleries were not profitable this year considering the reduced overhead costs—including flights, hotel stays, hosting parties and dinners, and shipping works of art to and from fairs—that the pandemic forced upon many. The abrupt standstill was needed across all levels of the art-selling community, a downtown gallerist tells The Art Newspaper. “We all needed time to analyse our businesses, our industry as a whole, and to really look at the positives and negatives of this global calendar we created.”

Like it did for many of us, the pandemic gave art sellers the time to reflect on what was important. “The most significant lesson we can all take from the pandemic is to be more considerate about how we invest our resources—financial resources, certainly, but more importantly, how and where we want to devote our time and our mental and physical energy,” says Amelia Redgrift, the senior director of global communications and content at Pace. “This thinking applies to decisions we make as a business as well as decisions we make as individuals. Most likely, this will mean ‘doing more by doing less’—valuing quality over quantity in every endeavour.”

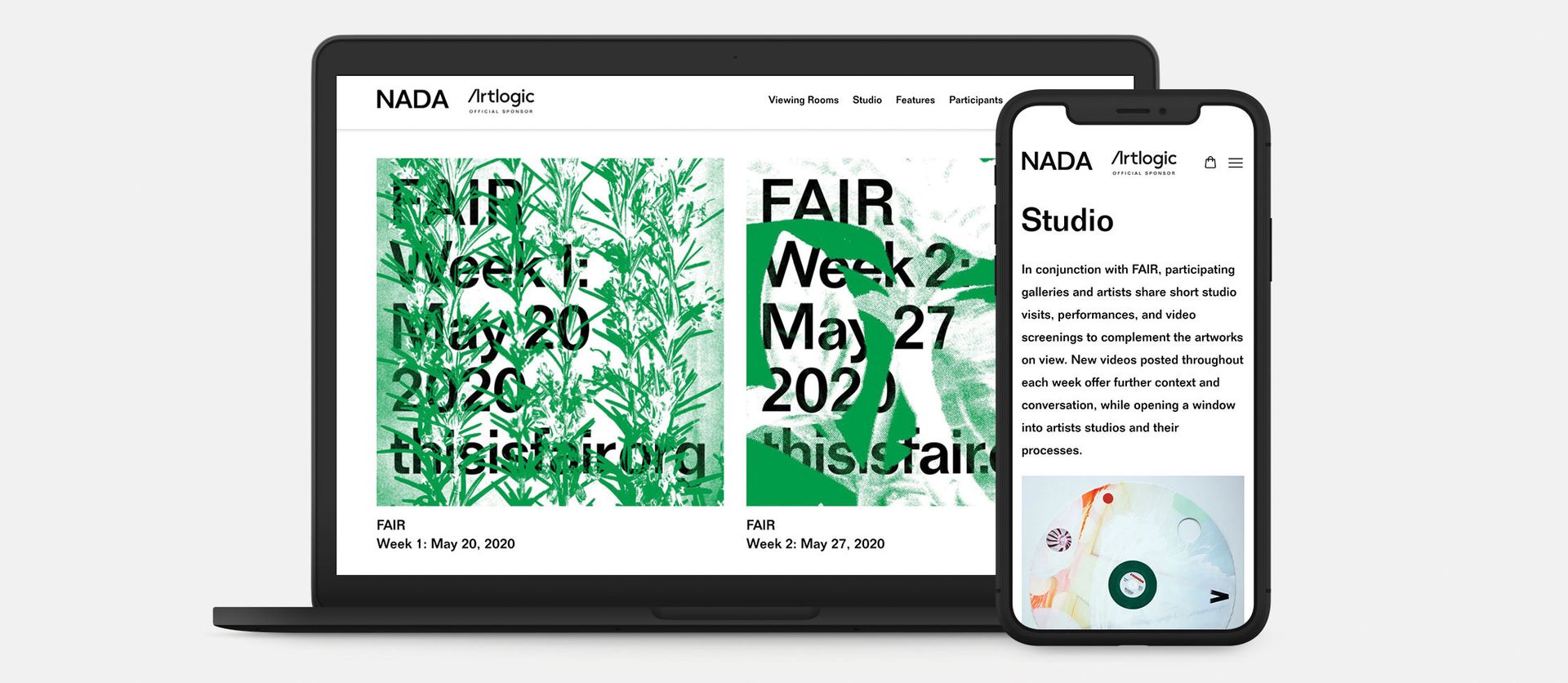

Artlogic's Online Viewing Rooms for NADA

For many galleries, that may mean a future with fewer art fairs. “Are we going to be more selective, yes,” says the gallerist Sean Kelly, who is showing at the Armory. “What we have to learn is how to balance the sense of neurosis between having to be everywhere and the sheer facts of the bottom line. What we should all hope for is a more civilised schedule, one that is less driven by commercial fixed points in the annual landscape and more by bodies of work. In many ways, Covid levelled that competitive mindset so prevalent in the art world and allowed us to ask, ‘What do we want to do? What’s best for our business, for our artists?’ We have to make the right decision for us. It’s as if there’s been a great culling of the sense that you have to be present at everything or else you don’t exist.”

“What we are all looking at is how to adopt this increased pace, but in a thoughtful way that retains what we’ve learned over the past year and a half,” says Nick Olney, a director at Kasmin Gallery, another Armory exhibitor. “OVR versions of your booth or digital attendance at a fair expands your reach to clients who can’t necessarily attend every fair. They can still meaningfully engage with the work. We’ve all been adapting these digital experiences on the fly. All these advances were done in real time, like upgrading a car while driving 80mph. But there’s really no substitute for in-person fairs and the excitement and serendipity that comes with them. In New York we feed off the tempo of fairs and exhibitions, the pace and the vibrancy. We all feed off that energy. It’s going to be about finding the right mix going forward.”