The charismatic John Cooper wanted his students to “paint what was all about them, say, a dingy bedroom, and look at it in a new way”, according to his friend and fellow artist, Nancy Sharp. The now little-known artist made a big impact on the group of mostly self-taught, working-class, part-time painters who came to his night classes at institutes in London’s Bethnal Green and Mile End during the 1920s and 1930s.

Many of Cooper’s students would go on to make a name for themselves as part of the East London Group. The standout artists of the group included Harold and Walter Steggles, two brothers who worked as clerks; Cecil Osborne, a council draughtsman; Elwin Hawthorne, a wages clerk; and Albert Turpin, a window cleaner who would go on to be elected mayor of Bethnal Green in 1946.

Grove Hall Park, Bow (1933) by Walter Steggle's brother, Harold

The group’s most characteristic works are atmospheric, sensitively observed paintings of their immediate surroundings: brooding street scenes in Mile End and Clerkenwell, canal and river views in Bow and New Cross, gloomy interiors that show their hard-up circumstances. At their best, the artists have something of the melancholy of Edward Hopper and the quasi-naive style of Maurice Utrillo. Comparisons can also be made with two other urban-inspired London groups: the earlier Camden Town Group and the contemporaneous Euston Road School—some of whose prominent figures, including Walter Sickert and William Coldstream, made the journey east to lecture to Cooper’s classes and became members themselves.

The East London Group made its mark with an exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1928 and its ascent was rapid, with artists finding their work increasingly sought after, both by national collections and private buyers at exhibitions in the West End. The group’s high point was arguably the participation of Hawthorne and Walter Steggles in the 1936 Venice Biennale.

Elwin Hawthorne's Bow Road (1932)

Cooper died in 1943 during the Second World War and the East London Group’s upward trajectory was rapidly curtailed, to the point that they practically vanished from the art world’s collective memory. “To be blunt, after the war, the world was moving into the jet age, the space age, electronic age,” says Alan Waltham, the curator of a new exhibition about the Steggles brothers and the East London Group at the Beecroft Art Gallery in Southend-on-Sea. “Most likely what the group were doing pre-war looked decidedly old hat. Whatever you’re doing has to appear to be relevant, otherwise people will move on.”

In recent years, a gradual rehabilitation has taken place, thanks partly to the indefatigable efforts of Waltham, who married the Steggles’s niece, and the family found themselves in possession of all of the brothers’ remaining paintings and documentation after Walter’s death, in near artistic obscurity, in 1997. Waltham also acknowledges the impact of David Buckman’s 2012 labour-of-love book From Bow to Biennale: Artists of the East London Group. “Without that, we wouldn’t be talking about them today,” he says. Waltham picked up the baton and nurtured the group’s newly burgeoning profile, helping to mount an exhibition in 2014 at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow, East London, and setting up a successful Twitter feed (@EastLondonGroup).

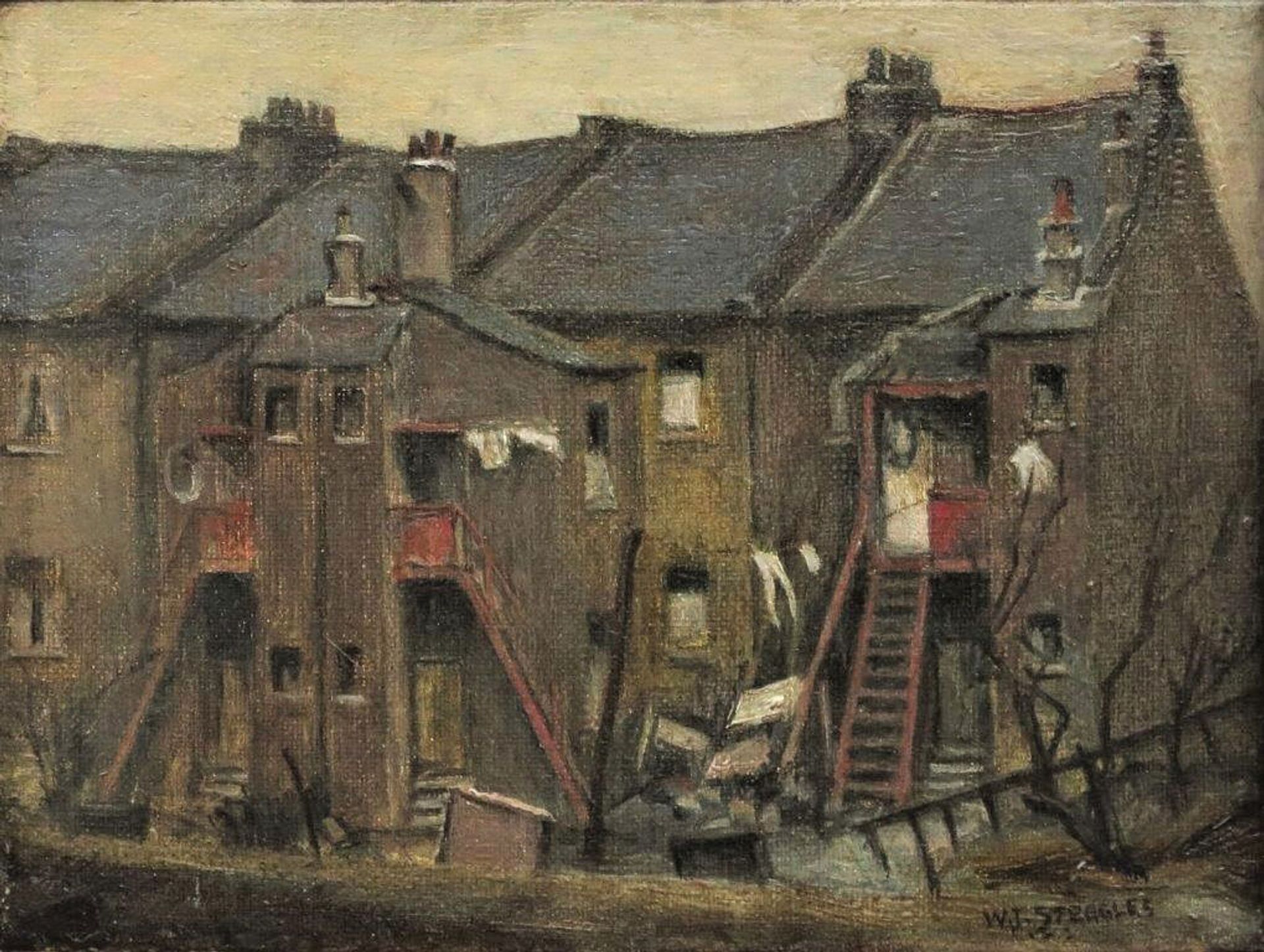

Walter Steggles's Old Houses, Bethnal Green (1929)

And why the resurgence of interest now? Waltham says that there has been a “reasonably rich vein of timing”, with a general renewal of attention in interwar art, and a particular convergence with the contemporary literary and cultural activity of London’s East End. Waltham also credits the simple fact of nostalgia or recognition. “It is very often the hook that draws people in: they remember a particular location, whether it’s because of work, or family history, or whatever. And once they start seeing the spread of work, they get fascinated.”

• Brothers in Art: Walter and Harold Steggles and the East London Group, Beecroft Art Gallery, Southend-on-Sea, 11 September-8 January 2022