In his book A Fool’s Errand, the often-harrowing tale of his 11-year mission to create the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Lonnie Bunch recalls sitting down with a Smithsonian Institution oversight committee to discuss planning. At the time, the museum, approved by Congress in 2003, had no site, architect, staff, collection or budget.

The mood was not encouraging. “To me, the gathering should have been named the ‘slow it down, we did not really want to do this’ committee,” the African American museum’s founding director wrote. “Often it felt as if the group’s function was to criticise, grouse and stonewall while wringing their hands at the task before them.” Bunch prevailed, opening the majestic $540m museum designed by David Adjaye in 2016 on the National Mall in Washington, DC, and it has proved a resounding success with visitors and scholars.

Now, the Smithsonian faces the gargantuan task of launching two more museums, the National Museum of the American Latino and the American Women’s History Museum, and Bunch is determined to help their future directors navigate the bureaucratic and financial hurdles. Legislation creating the museums was approved by Congress last December after decades-long campaigns by proponents.

Having been appointed in 2019 to lead the entire Smithsonian—19 museums, 21 libraries and the National Zoo as well as research centres and education units—as secretary, Bunch now has sweeping institutional clout in addition to the know-how he acquired in negotiating with Congress, wary donors and an architectural team to make the African American museum a reality.

Lonnie Bunch, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Previously he was the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture Stephen Voss, Smithsonian Institution

“I will not micromanage, but I will be a resource” for the directors, Bunch said in an interview. “I will be very cognisant of the bureaucracy, trying to make sure that when things need to get pushed through, they are.”

Half of the money for the museums will be allocated by Congress and half will be raised privately: estimates vary widely, but each is expected to cost significantly more than the $540m African American museum.

Bunch says that a search is under way for the directors and that he hopes to name both—“people who have a vision, who have a passion” for Latino and women’s history, and ideally a talent for fund-raising—by the end of the year. For now, both embryonic institutions are overseen by interim leaders.

A crucial qualification will be “stamina” for a process that could last 10 years or more, he says, as well as a recognition that each museum is a “two-sided coin”. While the new museums will celebrate the accomplishments and resiliency of American women and Latinos, they will also present painful, unvarnished stories about US history and American identity paralleling the narratives about slavery and racial segregation featured at the African American museum. “I really want that kind of raw duality from the leadership, and I will work with them to make sure that happens,” says Bunch, a historian.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture, near the Washington Monument Alan Karchmer, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Yet the biggest challenge may be deciding where each museum will be built. The remaining acreage on Washington’s National Mall, which Bunch described as “the promised land” in his book, is limited, and some of it is controlled by federal agencies like the National Park Service or the Department of Agriculture that may resist yielding the space.

The legislation suggested four potential Mall sites for consideration for the Latino museum and three for the women’s history museum, but made clear that “any other appropriate location” could be chosen. A site on the Mall near the Washington Monument and across from the African American museum was mentioned for both new museums, raising the potential for conflict; similarly, the Smithsonian’s existing Romanesque Arts & Industries Building, dating from 1881, was proposed as a site for the Latino museum in the legislation but is now being weighed by the women’s history museum as well, says Lisa Sasaki, the latter’s interim director.

The Smithsonian's Arts and Industries Building, which has been broached as a potential site for a Latino or women's history museum © Ron Blunt Architectural Photography

“I do recognise how important it is symbolically to be on the Mall,” Sasaki said in an interview. “But is the prestige and symbolism of being on the Mall worth potentially giving up on some of the things”—including more space—“that we might see if we were able to go a block off the Mall? Those are all conversations we’re planning on having.”

A lobbying group known as the Friends of the American Latino Museum has plowed its energy into campaigning for a Mall location. “There is too much at stake for current and future generations—Latinos and Americans of all backgrounds—not to see the Latino story represented on the most influential promenade in the US,” says Estuardo Rodriguez, president and chief executive of the group.

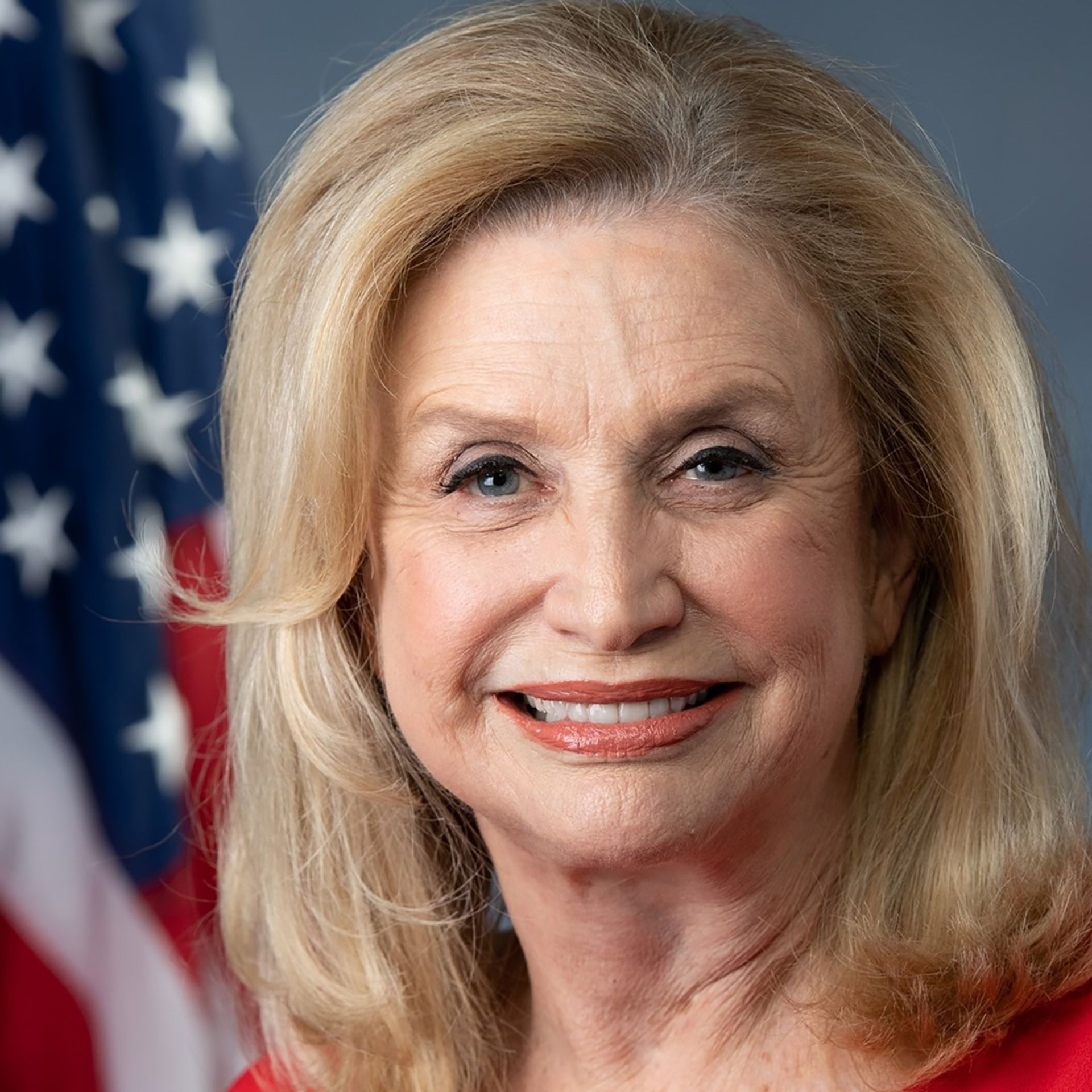

Meanwhile, Representative Carolyn Maloney, a New York Democrat who has been fighting for the establishment of the women’s history museum since the 1990s, says that locating it anywhere but America’s so-called “front lawn” would be a travesty. “I personally will fight until women are given the dignity and respect they deserve–on the Mall,” Maloney, a sponsor of the House legislation to create the museum, said in an interview.

The New York congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, who has campaigned for the creation of a women's history museum since 1998

The decision on the site will be made not by Congress but the Smithsonian’s 17-member Board of Regents, which includes six lawmakers and the chief justice of the Supreme Court as well as corporate executives and such figures as Michael Govan, director and chief executive of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Clearly, the board will have to juggle the needs of the two museums.

The architectural engineering firm Ayers Saint Gross, reporting to the board, will evaluate criteria such as environmental impact, pedestrian flow, proximity to transportation like Washington’s Metro system and potential threats like the rushing groundwater that added tens of millions of dollars to the cost of the African American museum’s foundation.

On the fund-raising front, the museums are expected to solicit energetically from charitable foundations: the Lilly Endowment, the Oprah Winfrey Charitable Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation were among the many that helped jump-start the African American museum. The advisory boards appointed recently for the two new institutions are expected to play a major role in raising money as well: as Bunch noted in his book, Winfrey became the largest donor to the African American museum as a member of its advisory council.

Among those who will leverage their connections and influence as part of the Latino museum’s 19-member board of trustees are the musician Emilio Estefan, the actresses Eva Longoria and Sofia Vergara, the broadcast journalist and anchor Soledad O’Brien and the president of Coca-Cola North America, Alfredo Rivera. The 25-member council advising the women’s history museum has enlisted such influential names as Billie Jean King, the actress and singer Lynda Carter, and Abbe Raven, the chairman emeritus of A+E Networks.

The actress Eva Longoria at a Hispanic Heritage Month event last September in Kissimmee, Florida, featuring Joe Biden, who was running for president Associated Press/Patrick Semansky

Then there will be the delicate dance with presidential administrations and with Congress. The White House Office of Management and Budget initiates Congressional funding requests for federal institutions, and Bunch has noted that President George W. Bush played a pivotal role from 2005 to 2008 in drumming up money for the African American museum that lawmakers had promised but not committed. (Later, the museum benefitted from a perception in Congress that Bunch enjoyed a direct pipeline to President Barack Obama, the Smithsonian secretary wrote in his book.)

The Biden administration supports the drive to create both institutions. For fiscal 2022, which began on 1 July, the Latino museum secured a congressional start-up allotment of $3.2m, while $2.5m was provided for the women’s history museum. Bunch hopes the money will flow quickly into creating an identity and exhibits for the museums online, forming a strong staff and recruiting consultants to assist with fund-raising and with building constituencies. “The idea is a strategy of visibility, thinking about the ways to not only get the word out, but get people excited,” he says.

“We’re beefing up our advancement operations right now,” says Eduardo Díaz, the interim director of the Latino museum, so that when a director takes over, “she or he has a team”.

Eduardo Díaz, the interim director of the National Museum of the American Latino and the head of the Smithsonian Latino Center Smithsonian Institution

Both Maloney and Senator Bob Menendez, a New Jersey Democrat who sponsored the legislation for the Latino museum, suggest that future Congressional allocations for the institutions will not be a struggle. Both note that the bills drew support from both Democrats and Republicans, despite a notable blip last December when a lone conservative Republican from Texas, Mike Lee, managed to block a unanimous voice vote on both museums in the Senate. (Lee argued that the museums would “weaponise diversity” and divide the nation.)

“We are now building on our bipartisan efforts and working to mobilise our diverse coalition of supporters to secure the funding levels needed,” Menendez said in an email.

Among the other formidable tasks facing each museum is forming a collection. Bunch and his staff at the African American museum eventually assembled around 40,000 objects, including such striking rarities as a shawl given by Queen Victoria to Harriet Tubman and a bible that belonged to Nat Turner, the leader of an 1831 slave insurrection. But at the start of their acquisitions drive, they feared that a sufficient number of African American artefacts might not have survived.

That led to a campaign to persuade African Americans across the country to search through their attics, basements and family records, and to Smithsonian training sessions in which owners were coached on preserving fragile objects. Reaching out to communities “creates a conversation around history that is really important for this nation,” says Bunch, adding, “It’s not just about the Smithsonian acquiring things, it’s helping the country preserve its patrimony.”

The Latino museum is expected to absorb the contents of the Molina Family Latino Gallery, a 4,500 sq. ft exhibition space that is expected to open at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History next spring. The gallery is the brainchild of the Smithsonian Latino Center, which is headed by Díaz and has been striving since 1997 to promote Latino history and culture across the institution’s museums and beyond.

A rendering of a gallery in the planned Smithsonian Latino Center, which will open next spring and serve as a precursor to the National Museum of the American Latino Courtesy of the Smithsonian Latino Center

Beyond that, the museum is not expected to harvest objects from the Smithsonian’s network of institutions, however. Bunch says the Smithsonian will ensure “that there is never a moment that all things Latino are in one museum, or that all things about women are in one museum”. From the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum to the National Portrait Gallery to the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, women and Latinos must be incorporated into each institution’s narrative, he says.

Or, as Sasaki put it, the creation of the new entities “should not let other museums off the hook”.

Still, Díaz says he hopes that the founding of the museums will lead to more “fluidity” in sharing objects across the sprawling Smithsonian network. Should the new Latino museum want to borrow the jersey of the Puerto Rican baseball star Roberto Clemente from the National Museum of American History, “I’m hoping that people will say, hey, the jersey is in good shape, it’s not in conservation, it’s not on exhibit, it’s not on loan, so yeah, here it is,” he says.

While the Latino population in the US is the nation’s largest minority, numbering over 60 million, it has long been given short shrift in museum presentations. Scholars and curators expect the new museum to forge an eye-opening narrative about the role of Latinos in political life, the legal system, commerce, medicine, business, the military, the arts, agriculture, gastronomic culture and myriad other areas by enlisting the help of experts in those fields and delving into historical records.

The museum is likely to chart the history of the Latino presence in America, which dates back to the late 15th century, well before the British arrived; track diverse patterns of migration to the US involving dozens of countries; and address a history of oppression and discrimination that long blocked Latinos from advancing.

The women’s history museum will build on the progress of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, also known as “Because of Her Story,” an online effort created in 2018 that aims to amplify a diversity of women’s voices among the Smithsonian’s many museums and affiliates as well as other venues. That initiative is not a collecting entity, however, so the museum director will likely start from scratch in building a collection.

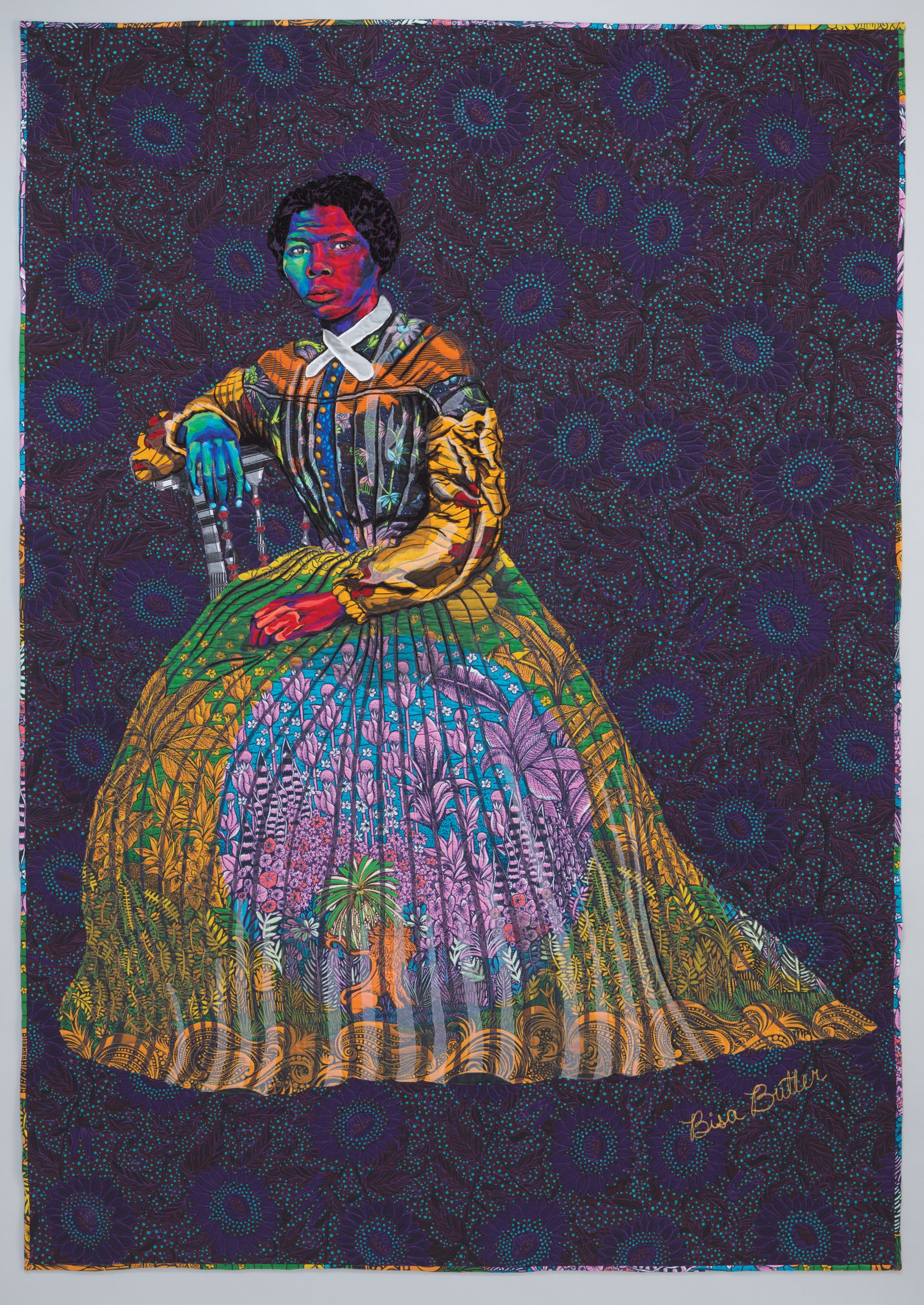

Bisa Butler's I Go To Prepare A Place For You (2021), a portrait of Harriet Tubman on textile that was purchased through the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative for the National Museum of African American History and Culture © Bisa Butler, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Current exhibits at the Smithsonian related to the initiative include presentations at the National Museum of American History on female inventors and entrepreneurs, women’s suffrage, women’s “invisible labour” and the history of girlhood, as well as a focus on female Supreme Court justices and civil rights figures at the National Portrait Gallery.

Still, there is a mountain of neglect to rectify: Maloney points out that there is no comprehensive museum in the US dedicated to the full story of the history of American women; only nine of 100 statues in the US Capitol’s National Statuary Hall depict women; only 5% of some 2,400 national monuments honour women; and women are markedly underrepresented in books ranging from history texts to formative children’s stories.

For the new museum, Sasaki has her hopes pinned on a transformative narrative: she wants its collection and exhibitions to “redefine our definition of heroes, especially when we look at women”. Rather than simply singling out women who won medals or awards, she imagines that the new museum’s content will explore struggle as part of the story. Every single day,” she notes, “women across this country do things that defy expectations, that question the limitations of what has been set upon them.”

Lisa Sasaki. the director of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. She is currently serving as interim director of the Smithsonian Women's History Museum Courtesy of Lisa Sasaki, Smithsonian Institution; © Terry Lorant Photography

Bunch says he will labour to ensure that both institutions protect their curatorial independence. Shortly after the African American museum opened in 2016, a resolution was introduced in the House to censure him because some lawmakers felt that the museum paid inadequate attention to the Black associate Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas. Bunch was accused of a liberal bias against a conservative jurist.

Ultimately the measure never came to a vote, but the threat posed to the Smithsonian’s curatorial integrity made an impression. “I think there will always people, in Congress and out, who have a vision of what these museums should be, what stories they should tell,” Bunch says. “But first and foremost, they are shaped by scholarship. And I will fight to make sure that's the case with these two museums.”

Will the new institutions take as long to open as the African American museum, which welcomed the public 13 years after it was approved by Congress (and 11 years after Bunch was appointed as founding director)? “I think that the reality is that you shoot for a decade,” says the Smithsonian secretary. “And then, see what happens.”