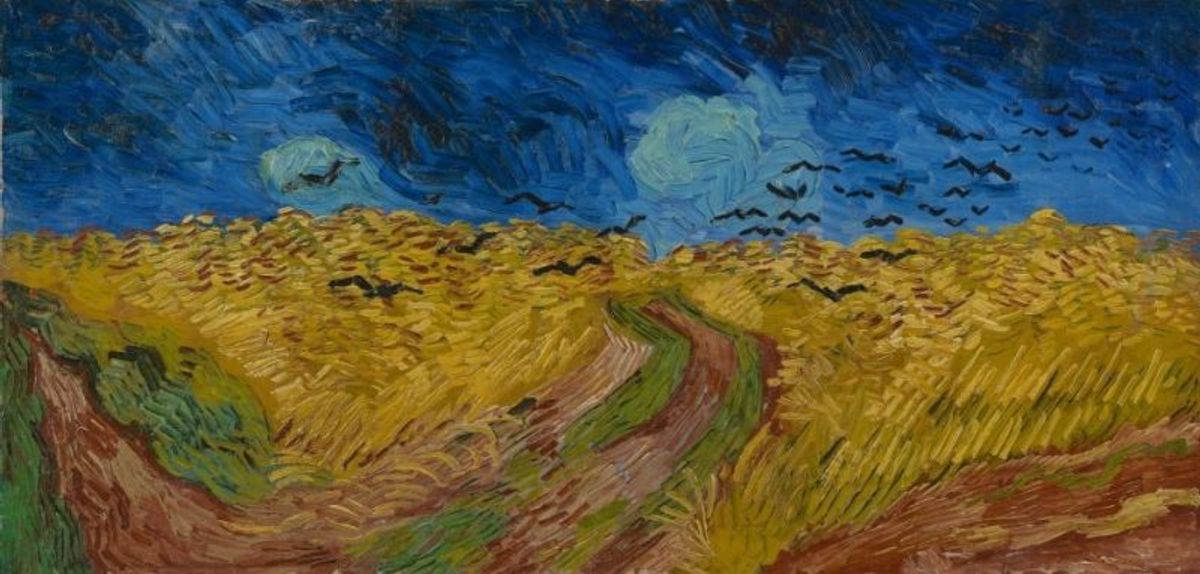

Wheatfield with Crows has traditionally been regarded as Van Gogh’s last painting, with ominous birds swooping beneath a stormy sky. But although dating from July 1890, the month of the artist’s death, the idea that it was the final picture in a myth. Recent research shows that the work he painted the morning that he shot himself was actually Tree Roots.

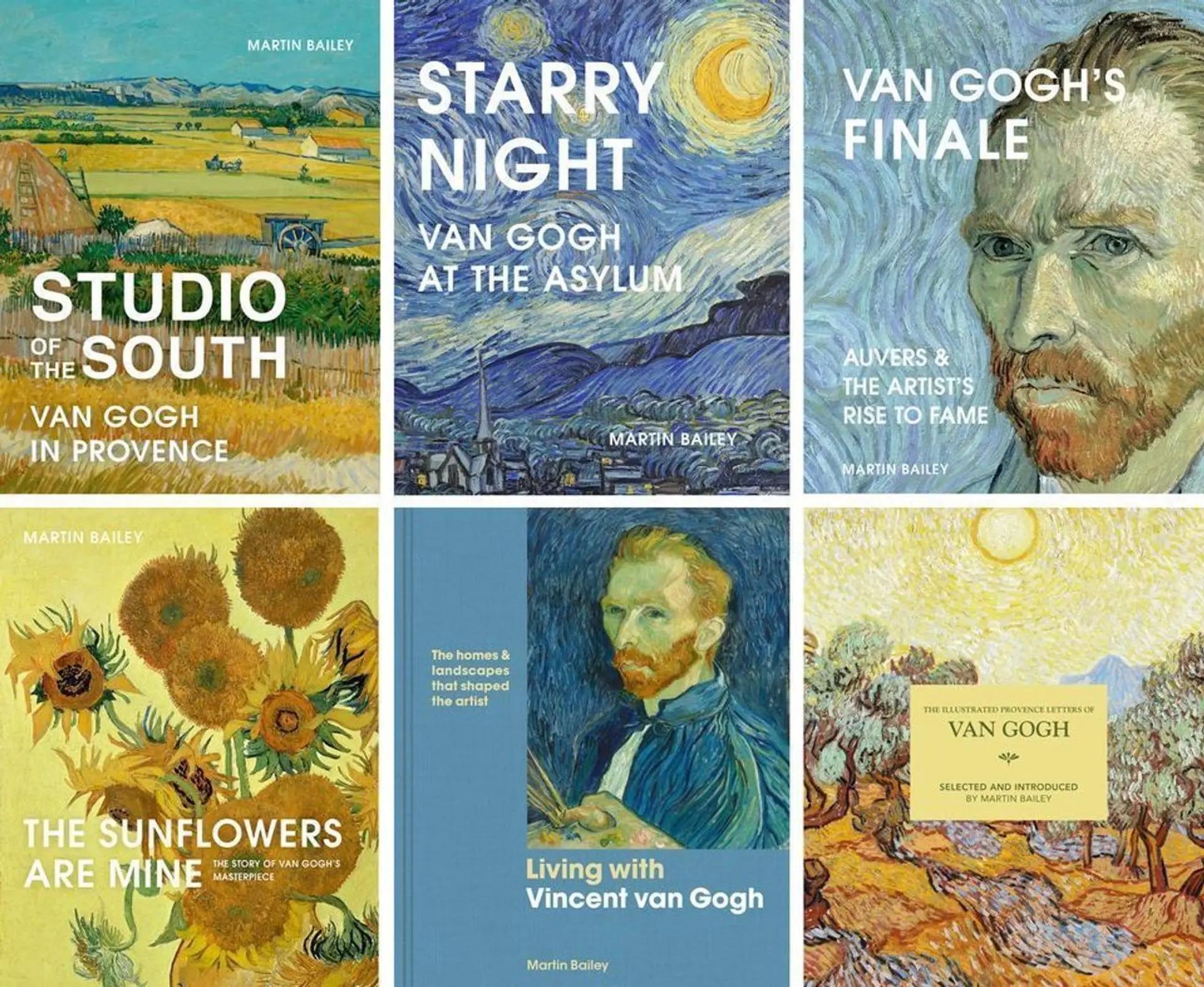

In my new book Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (to be published on 21 September) I set out to examine Wheatfield with Crows afresh. Once one accepts that it is not the last picture, its subtleties begin to emerge.

Vincent loved the wheatfields on the plateau just above Auvers-sur-Oise, the village to the north of Paris where he lived for his last ten weeks. The fields lay just five minutes’ walk from the inn where he lodged. He would often go there, either for a stroll and a chance to think—or to work.

Although the link does not seem to have been spotted before, a similar landscape to Wheatfield with Crows was captured by Charles-François Daubigny (1817-78), an earlier artist who had lived in Auvers and was greatly admired by Van Gogh.

In Daubigny’s The Track on the Plain of Auvers, the small figure of a painter sits under a sunshade with a path heading off towards distant trees, probably those surrounding the village. Van Gogh may even have set up his easel on this very path. It is very unlikely that he knew this particular Daubigny painting, but the two artists were equally attuned to the beauties of the Auvers landscape.

Charles-François Daubigny’s The Track on the Plain of Auvers (1843) Private collection

Both works were probably painted in July, since the corn has ripened, but has not yet been harvested. Despite their common subject matter, the two pictures could hardly be more different. Daubigny’s calm and bucolic scene captures the heat of a summer’s day, with an artist protecting himself under a sunshade. Although barely visible, the diminutive figure of a woman walks away towards the leafy trees.

Wheatfield with Crows emphasises just how much art had moved on since Daubigny’s conventional 1843 painting. Van Gogh’s Expressionist picture is full of foreboding. Although the crows are probably making their escape, one almost feels that they are swooping down on the viewer. The three diverging paths appear to be going nowhere, ending abruptly after veering away. The strangely coloured sky could hardly be more agitated, with a thunderstorm about to break over the eerily luminous wheat. No people appear in this unsettling scene.

The wife of Vincent’s brother Theo, Jo Bonger, certainly interpreted the picture as threatening. She recorded in her memoir: “As his last letters and pictures show”, the catastrophe approached “like the ominous black birds that dart through the storm over the wheatfields.” When writing decades after Vincent’s death, Jo was only too aware of what had occurred so soon after the painting: the fatal shooting.

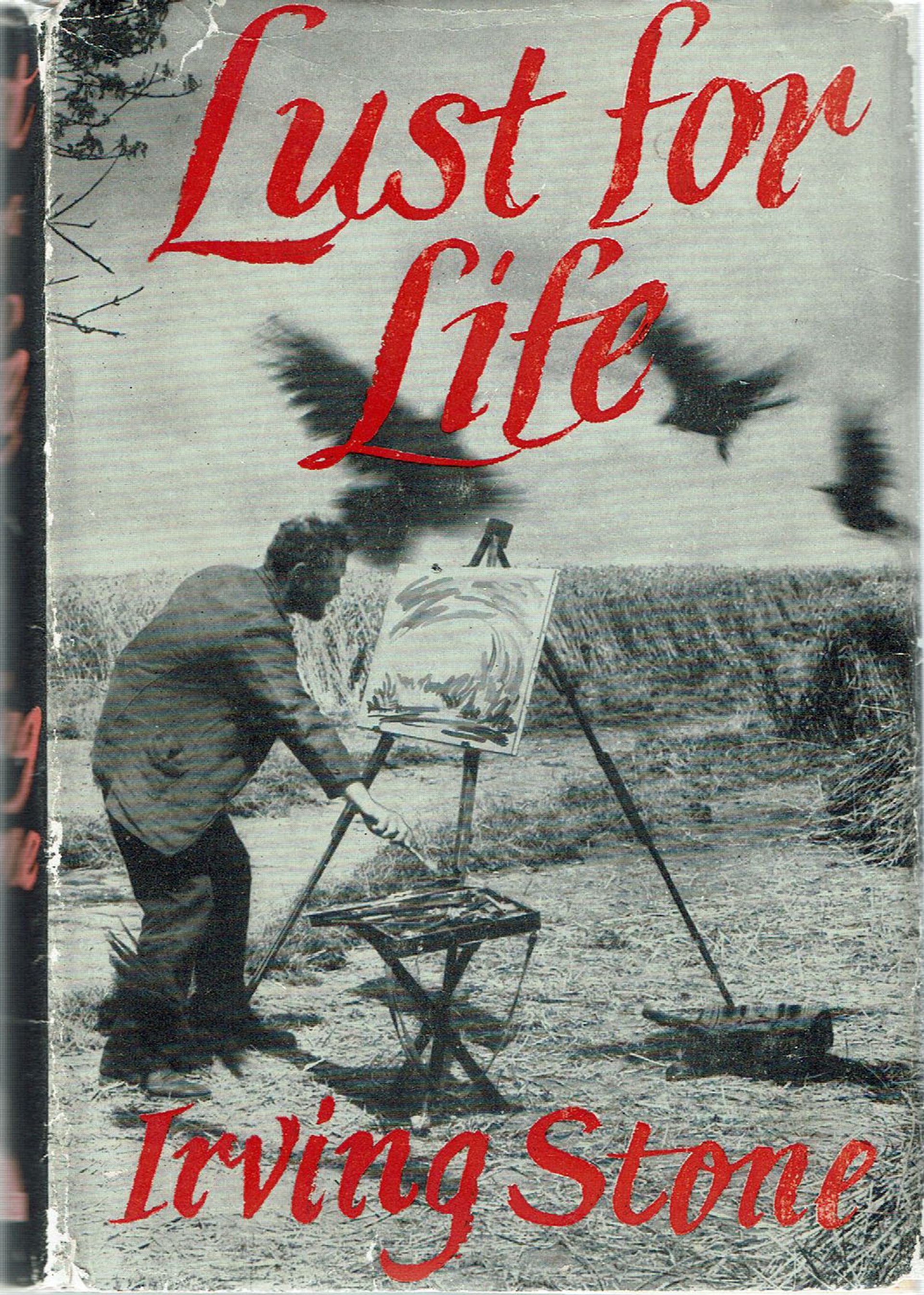

Book cover for Irving Stone’s Lust for Life, depicting one of the last images in the film, 1956 John Lane publisher, London

What really fuelled the link between the painting and Van Gogh’s death was Irving Stone’s 1934 novel Lust for Life and the subsequent 1956 film. Kirk Douglas, who played Van Gogh, stands beside an easel, hard at work finishing Wheatfield with Crows. While adding the final touches, a flock of birds suddenly takes flight from the field and swirls aggressively around him. Impulsively, Douglas paints the crows into his picture, with thick, black, stabbing strokes. He then staggers off, as the camera pans towards a nearby farmer ploughing. A few seconds later we hear the sound of a gun being fired: The End.

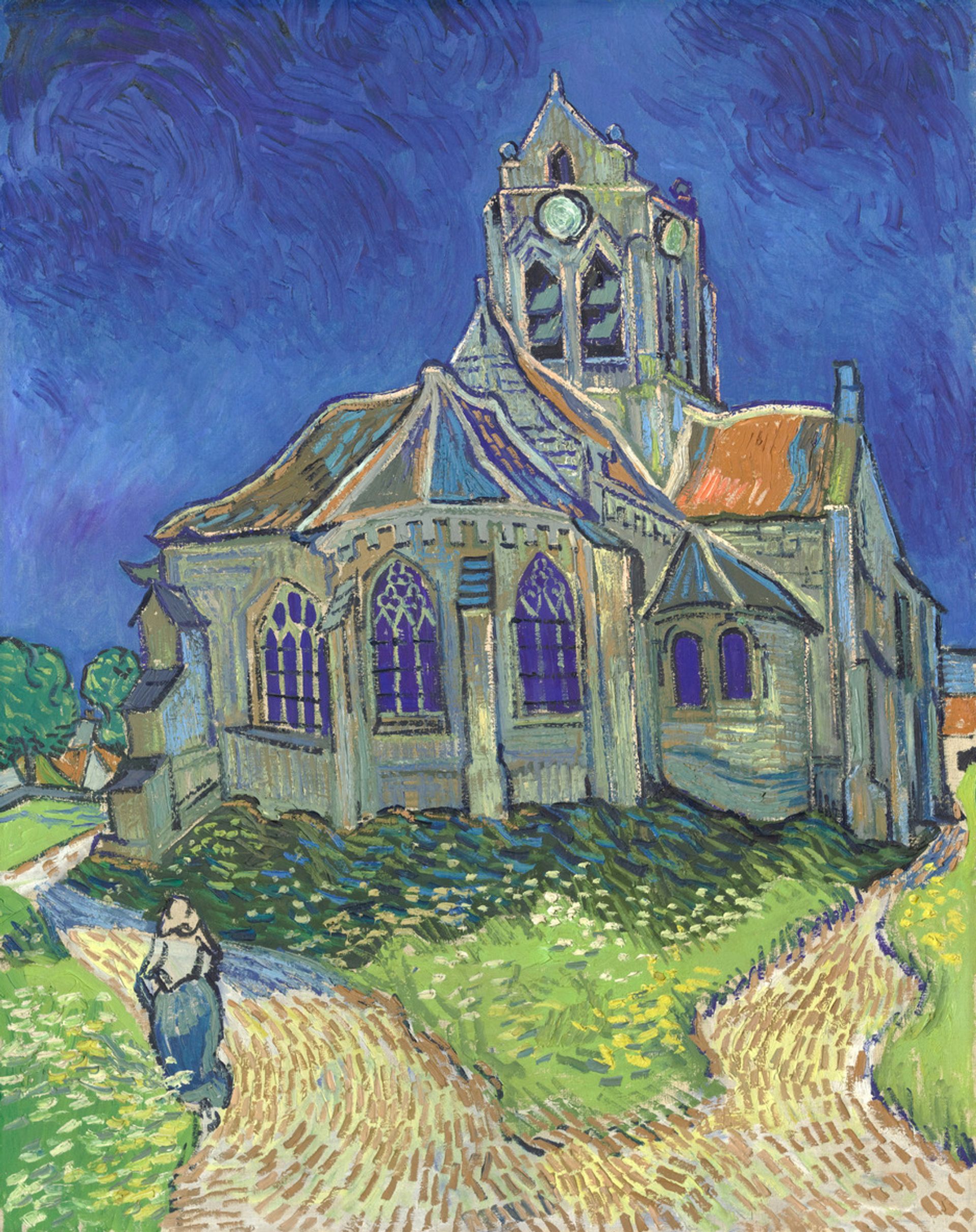

Wheatfield with Crows, painted quickly with confident brushwork, is undisputedly among Van Gogh’s most powerful works. But along with its sinister aspects, it is also full of life: the ripening and swaying wheat, the soaring birds and the volatile weather. Although the comparison is rarely made, the diverging paths are not unlike those in the much more restful Church at Auvers, completed just a month earlier.

Van Gogh’s Church at Auvers (June 1890) Courtesy of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

The spot where Van Gogh painted Wheatfield with Crows was probably just a few hundred metres to the north of the church, by a small track known as Sente du Montier. This location was captured in a 1950s photograph.

The probable spot where Wheatfields with Crows was painted Photo: Marc Edo Tralbaut, 1950s; courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum archive, Amsterdam

When in July 1890 Vincent painted panoramic landscapes in the plain above Auvers he described them in a letter to Theo and Jo: ”They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.”

Yet after Vincent’s words “extreme sadness”, he pulled back. In an apparent about-turn, in the very same paragraph, he added that “these canvases will tell you what I can’t say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside”. Vincent was both trying to reassure Theo and Jo about his psychological condition and expressing his love of the landscape.

Wheatfields had been one of Vincent’s favourite subjects in Provence, before his arrival in Auvers. Wheat held a deeply symbolic significance for him: farmers would sow seeds in autumn, the plants would sprout towards the end of the winter, the fields would turn green in spring, and finally the crop would ripen to a burnished gold in late July—ready for reaping. The harvest represented a time of plenty, although it temporarily left the fields bare and empty. And so the cycle of life would continue, year after year.

Three weeks after painting Wheatfield with Crows Vincent returned to the plateau one last time. In my book, I pinpoint the spot, just to the north of the wooded château grounds where the fields begin—and five minutes’ walk from the spot where he had depicted the diverging paths. A shot rang out. Van Gogh’s career came to a tragic end, but his art lives on.

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books, with Finale in the upper right

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. His latest publication is the reissued book The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: vangogh@theartnewspaper.com Please kindly refer queries about authentication of possible Van Goghs to the Van Gogh Museum.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.