Either visitors wander round the room for a minute or two, take a photo or selfie, then leave. Or else they sit down, look at the pictures for a minute or two, then take a photo or selfie and leave.

“I find it very depressing,” says Matilde Tomat, a psychotherapist based in Blackburn, northern England. She is at Tate Modern on a Sunday afternoon, watching how people experience the gallery devoted to Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals.

“You can’t get them to stay for two minutes in front of a painting,” says Tomat, who, unlike most other Tate-goers, is planning to study these sombre masterpieces of US post-war abstraction for at least an hour. “We don’t have the attention span. It’s become the generation of ‘now’. There’s no sense of depth of connection.”

It is, of course, a cultural commonplace to point out that in today’s distracted digital age most museum-goers spend less time looking at paintings than they used to. But the fact remains that the 21st-century art experience has become something very different from that envisaged by 20th-century artists such as Rothko, who, according to Tate Modern’s accompanying gallery text, regarded these monumental canvases as “objects of contemplation, demanding the viewer’s complete absorption”.

Things have changed and there is an increased need for embodied experience in art

Unfortunately for painters, standing in front of a picture is no longer enough. “Things have changed and there is an increased need for embodied experience in art,” says Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of the Castello di Rivoli contemporary art museum and the Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti, near Turin. Both institutions—set respectively in a semi-ruined ducal castle and the country retreat of a reclusive collector straight from the pages of Proust—offer, in contrasting ways, immersive experiences akin to entering a single, fantastical art installation. “People have such a passive experience of life through screens on mobiles and laptops,” Christov-Bakargiev says. “Therefore there’s an extreme need for experiential moments.”

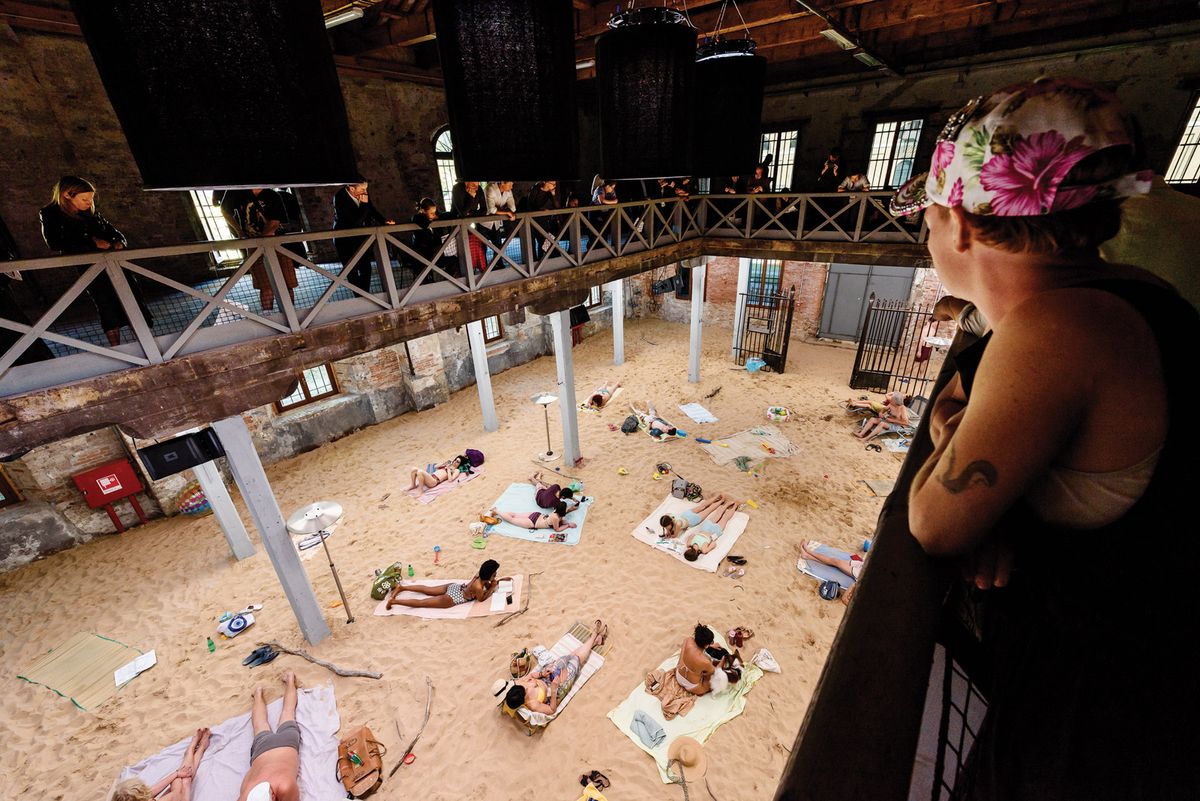

Performance and installation pieces are now the preferred media of just such moments at biennials and museum shows. For the second edition in a row, the top prize for a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale was won by a performance. Visitors had to queue for hours on Wednesdays and Saturdays for the chance to experience Lithuania’s Golden Lion-winning Sun and Sea (Marina), a mesmerising opera on an artificial beach that evoked the emotional and environmental nullity of long-haul tourism. The idea that a painter might win the Golden Lion now seems almost quaint.

Then there is Olafur Eliasson’s In Real Life at Tate Modern and Antony Gormley's blockbuster at London’s Royal Academy of Art, exhibitions that at times feel more like funfairs than museum retrospectives, inviting visitors to walk through a cloud and clamber through huge balls of steel wool.

But where does all this leave the commercial art world, which for centuries has relied on the passive contemplation of painting and sculpture to forge careers, reputations and fortunes? How do you monetise experiential art?

The market has responded, to an extent. Since 2000, the Unlimited section of Art Basel has been a showcase for large-scale installations. A second art fair exclusively devoted to performance pieces took place in Brussels in September. David Zwirner’s current Yayoi Kusama show in New York not only includes an immersive installation, but also the Japanese artist’s latest must-Instagram Infinity Mirror Room.

According to Marc Glimcher, the president and chief executive of Pace Gallery, the “emergence of the art experience, rather than the object” requires “a new approach, a new space”.

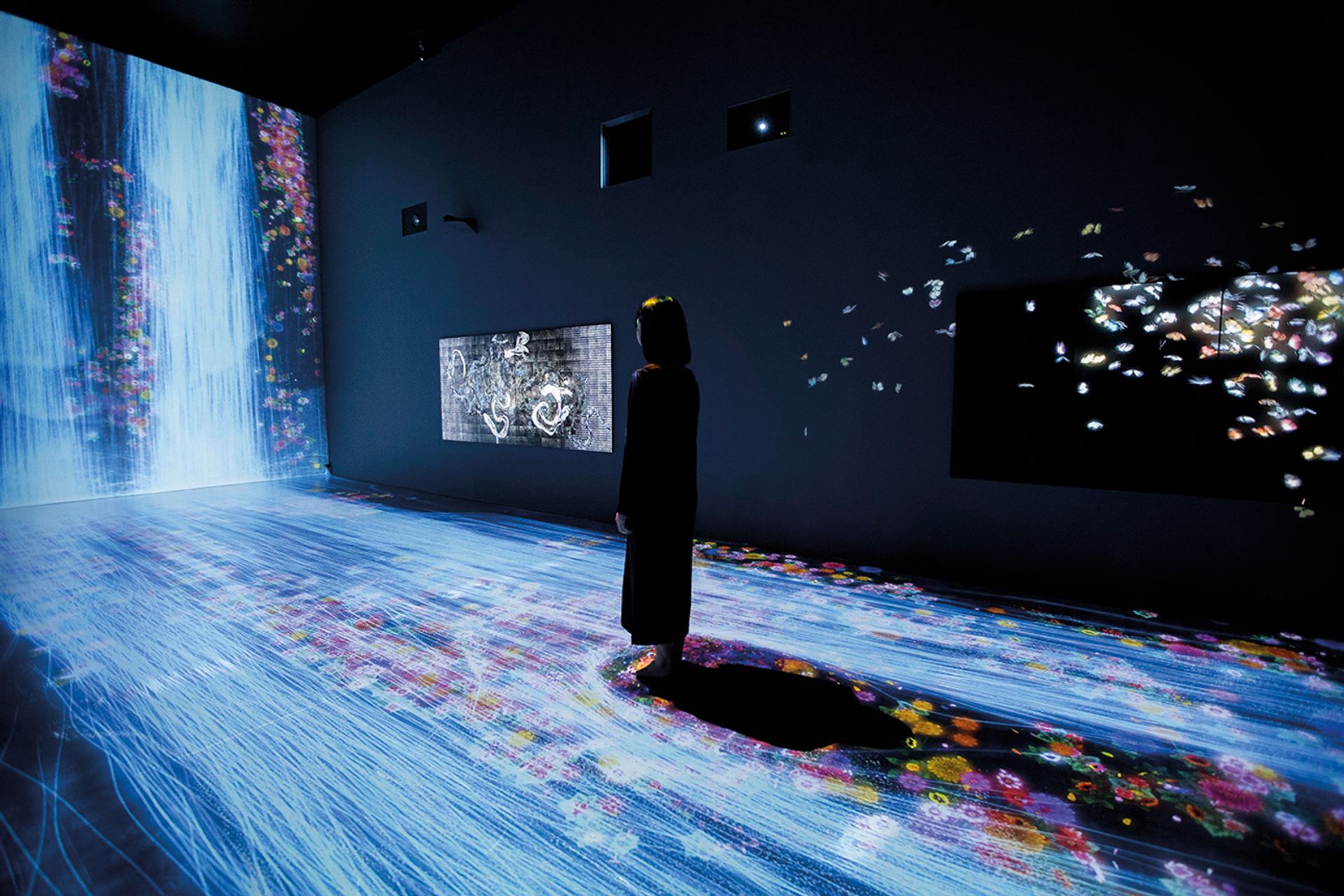

With that in mind, alongside launching the PaceX initiative devoted to tech- and experience-based art in August, the gallery has just opened a vast eight-storey, 75,000-sq. ft headquarters in Chelsea, New York. The seventh floor features a 2,200 sq. ft gallery dedicated to video, installation and performance that can accommodate around 150 people, although any of the larger viewing spaces can be given over to the next hugely popular immersive creations by multimedia groups, such as Random International and teamLab, both of which Pace represent. Installations such as teamLab’s Transcending Boundaries at Pace London in 2017, which featured a virtual waterfall, have helped expand the gallery’s social media profile.

“We have 800,000 Instagram followers and 1,000 clients. Art has become democratised,” says Glimcher, who adds that Pace currently has no plans to charge visitors to attend its installations and performances. But, he adds: “We’re still selling big expensive paintings. The models aren’t mutually exclusive.”

The Instagram-friendly installation of teamLab's Transcending Boundaries at Pace London in 2017 featured a virtual waterfall © Teamlab and Pace Gallery

While anyone can visit galleries such as Pace and Zwirner for free–and Instagram the works, giving the dealerships free digital publicity in the process—only a select few are able to buy them.

Those lucky enough to buy at Pace’s September sell-out show of nine abstracted figure paintings by the young US artist Loie Hollowell, for instance, would have been gratified to see a similar work from 2014 sell at auction in October for $440,000. Pace’s carefully vetted customers had paid $100,000 for Hollowell’s latest canvases.

In today’s hyper-financialised art world, in which wealthy collectors and speculators compete desperately to buy works by the latest fashionable, flippable names, the thrill of possession, rather than aesthetic appreciation, can become the primary experience.

And herein lies a problem. In 2017, the global management consultancy McKinsey & Company noted that in recent years US consumers’ spending on experience-related services had grown almost four times faster than equivalent expenditure on goods. “American consumers are consistently voting with their wallets to buy experiences rather than products,” it said.

The widely observed shift away from buying things, particularly among Uber- and Airbnb-using millennials, is not good news for the long-term prosperity of the art market. For the post-baby boomer generation, a high quality digital image that can be shared on social media is all that you need to “own” of a work of art.

“The physical world isn’t where they see the most exciting things,” says Michael Short, a Berlin-based art advisor, who wonders how the art trade is going to convert the digitally minded to the culture of collecting.

On two recent occasions, Short has met affluent thirty-somethings with tech-based wealth wandering, slightly bemused, around art fairs. One commented “it’s a way of turning money into trouble”, Short recalls. Another said collecting was “such a 19th century thing to do”.

“There will always be people who want to build private art collections,” Short says, but he thinks they will be an ever-decreasing minority. As for the rest, “the experience is just showing up, then leaving”, he adds. “We’re missing the experience of the cultural conversation.”

This November, Mark Rothko’s 1953 canvas, Blue Over Red, was among more than 800 works included in a vast retail display covering four floors and 40 galleries at Sotheby’s recently “reimagined” headquarters in New York ahead of the marquee autumn sales of Impressionist, Modern and contemporary auctions.

Estimated at $25m to $35m, the painting, not one of Rothko’s best, elicited passing remarks at the view such as “it’s very orange”, “wow, that’s expensive” and “it’s much smaller than I thought”. It was snapped on a few phones, as was the label. But in an environment that had more in common with Ikea than Moma, it was hard, if not impossible, to view the work as an “object of contemplation”. It sold on 14 November to a single bid of $25m (plus fees).

Is this the future of art’s “experience” economy? Or the past?